Twisting Traditions: Miwa Kyūsetsu XIII

The Legendary Family of Hagi

Twisting Traditions

One of the most remarkable achievements of contemporary Japanese kogei, and one which sets it apart from historical practices of the craft, is the notion of twisting traditions and established practices. It is what has enabled Japanese kogei to transition from a tradition where crafts were exclusively used for everyday utensils to the use of craft mediums to create original contemporary art. While traditions have been central to the craft, practiced generation after generation with little change—tea bowls in clay, boxes in lacquer, an obi (belt for a kimono) in weaving, and baskets in bamboo—Japan’s craftspeople have learned from their ancestors, apprenticed with master craftsmen, and passionately preserved their time-tested methods. In fact, they are expected to continue the inherited traditions.

It is the recent generation of craftspeople that has revolutionized that continuity and shaken this stability. They have begun searching for their personal voice, pushing boundaries and introducing new ideas. While remaining true to the methods of the craft—paying great respect to their heritage—they have introduced daring and fearless new means of expression, thereby becoming participants in the global movement of contemporary art. The craftspeople featured in this section about my journey in Japan have completely transformed traditions, introducing a new spirit and taking the world of Japanese crafts to new horizons.

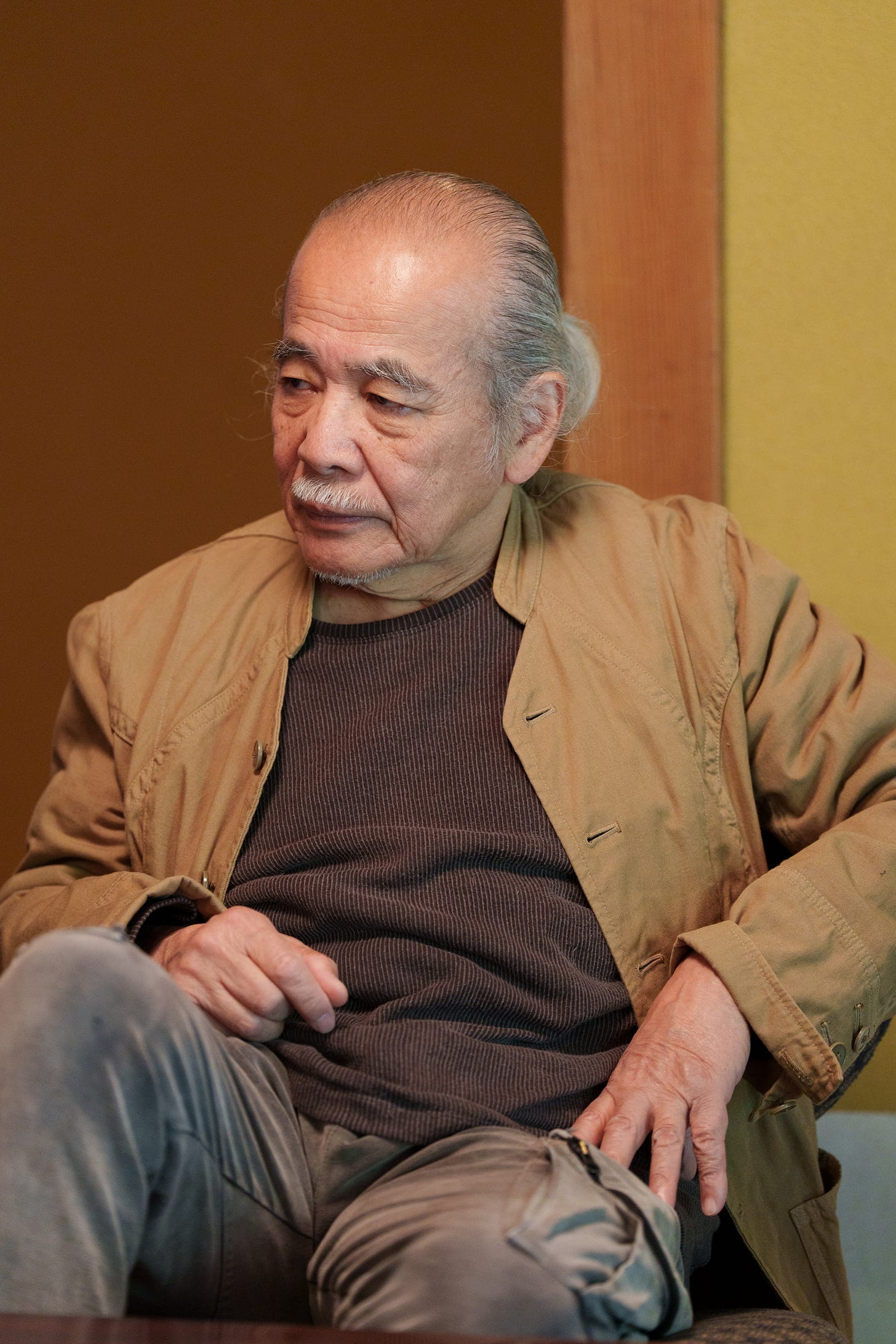

Miwa Kyūsetsu XIII (b. 1951)

Everyone in the picturesque coastal town of Hagi, lined with samurai-era residences, knows the Miwa family: the hairdresser in the town’s hair salon; the owner of the remarkable coffee shop; the founder of the hotel, the waitress in the small Yakitori bar. The Miwa family, who established its kiln in the 17th century, represents the aristocracy of Hagi ware, a celebrated family of an ancient artistic heritage, spanning thirteen generations of potters. The family is known for discovering the thick white ash glaze, which has become synonymous with Hagi-ware.

I was hosted by Miwa Kyūsetsu XIII, a thirteenth-generation potter and the head of the family, and by his ceramicist son, who is yet to receive the family’s title. Kūsetsu’s father was a National Living Treasure (Kyūsetsu XI), and his uncle is credited with developing Hagi’s distinctive white glaze. The family’s title signifies accomplishment, innovation, and leadership. He became Miwa XIII at 68. The family’s historic house and garden, where I joined him for a bowl of matcha, is the epitome of the traditional Japanese house – harmonious connection with the beautiful garden, tatami mat flooring, and sliding shoji doors. What an honor it was for me to sip a bowl of matcha in his robust tea bowl, sitting in the same room his ancestors lived and worked, and experiencing the allure of the place of peace and contemplation.

But Miwa Kyūsetsu XIII does not do it like anyone else in his family. His addition of two striking contemporary structures to the family’s compound embodies his innovative thinking and ability to think outside the box. His love for architecture has led him to commission new spaces—workshop and gallery—from Japanese architect Hiroshi Sambuichi, brilliantly integrated within the existing surroundings. These buildings symbolize his quest for integrating the contemporary with the traditional, and for his ability to twist traditions, which now defines his work. It was particularly surprising to learn that it is artistic elements from outside of Japan that came to play a role in his creative evolution.

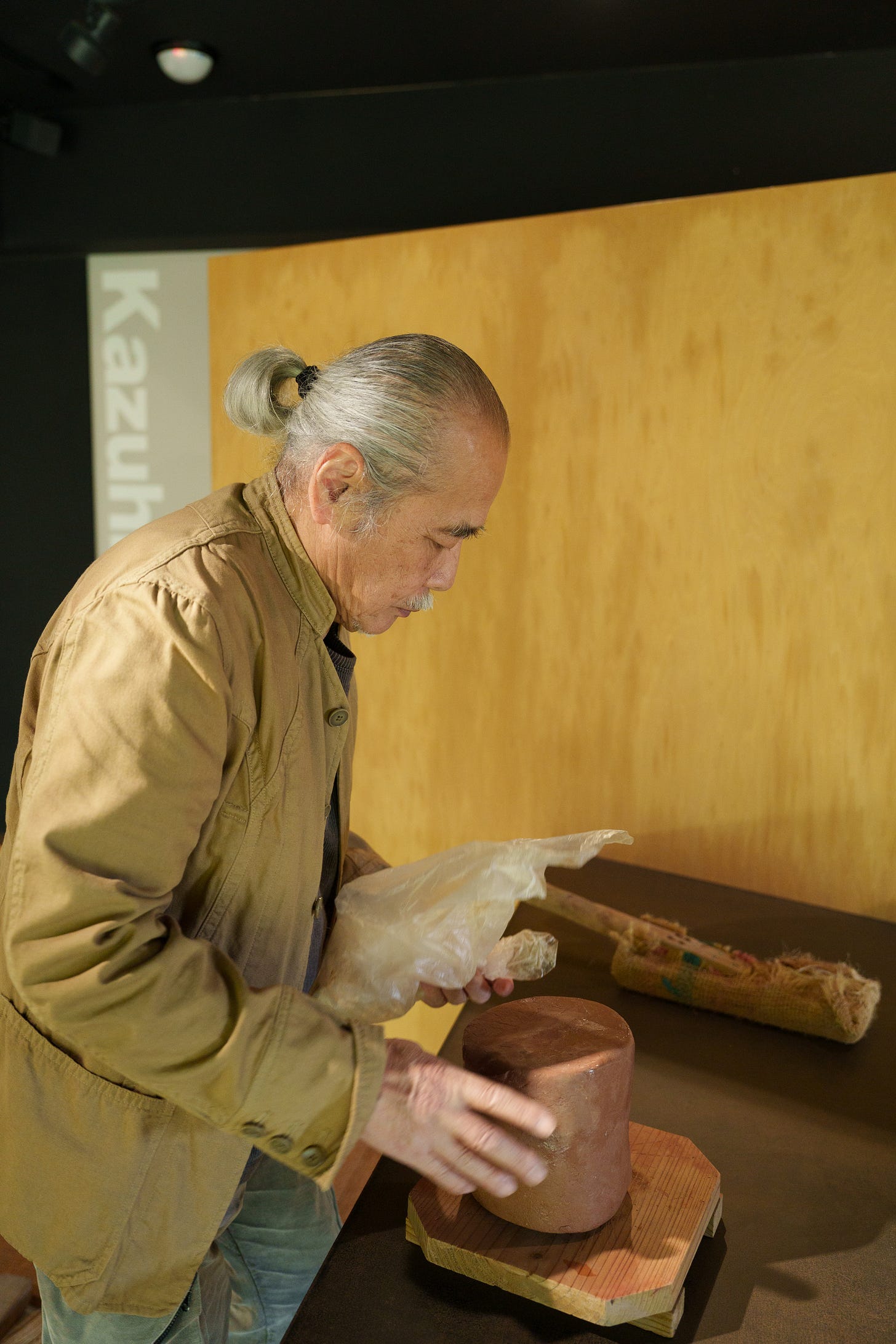

What Miwa Kyūsetsu XIII learned from the American Studio Movement enabled him to shape his personal language and entice the traditional Hagi-ware. In his journey to define his own voice and to create his expressive, bold forms, he was inspired by American artist Peter Voulkos, whose work he discovered as a teenager. It is from Voulkos that he learned to search for artistic freedom, for expressing the clay in a sculptural, emotional way, different from what he had seen in his father’s work. As the young son of one of Japan’s most prolific ceramicists, he studied at the San Francisco Art Institute, returning home with a fresh spirit, eager to experiment with new methods and new thinking, and to take Hagi-ware to new horizons. He began creating provocative, daring, and distorted forms, which were at first not readily accepted. However, throughout his career, he has established a distinctive language for which he is admired globally. While nature is present in all of his work, there is also a strong architectural sensibility, and his angular forms remind me of the visionary buildings that German Expressionists created in the 1920s. All of his pieces are partially covered with the iconic white Hagi glaze, revealing the red clay underneath, and making them special.

The titles of his pieces are poetic, bringing another layer to the experience. Some look like mountain landscapes covered with melting snow in the spring; others embody ancient granite monoliths; and some represent the open American Southwest landscapes that he saw when visiting the national parks. His son Taroh (b. 1984) has developed his own vocabulary and his vessels are sensual, covered with soft green glaze. I am eager to follow the path of his evolution.

Photography by © Takuro Kawamoto.

This visit was made possible by A Lighthouse called Kanata.

Beautiful! I was in Hagi last winter to see wild Camelia in bloom.

I wished to visit his studio.