Twisting Traditions

Maeta Akihiro: The New Voice in White Porcelain

Twisting Traditions

One of the most remarkable achievements of contemporary Japanese kogei, and one which sets it apart from historical practices of the craft, is the notion of twisting traditions and established practices. It is what has enabled Japanese kogei to transition from a tradition where crafts were exclusively used for everyday utensils to the use of craft mediums to create original contemporary art. While traditions have been central to the craft, practiced generation after generation with little change—tea bowls in clay, boxes in lacquer, an obi (belt for a kimono) in weaving, and baskets in bamboo—Japan’s craftspeople have learned from their ancestors, apprenticed with master craftsmen, and passionately preserved their time-tested methods. In fact, they are expected to continue the inherited traditions.

It is the recent generation of craftspeople that has revolutionized that continuity and shaken this stability. They have begun searching for their personal voice, pushing boundaries and introducing new ideas. While remaining true to the methods of the craft—paying great respect to their heritage—they have introduced daring and fearless new means of expression, thereby becoming participants in the global movement of contemporary art. The craftspeople featured in this section about my journey in Japan have completely transformed traditions, introducing a new spirit and taking the world of Japanese crafts to new horizons.

Akihiro Maeta (b. 1954)

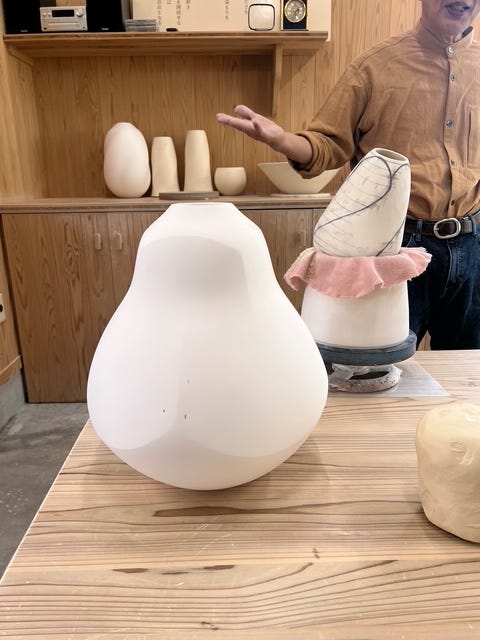

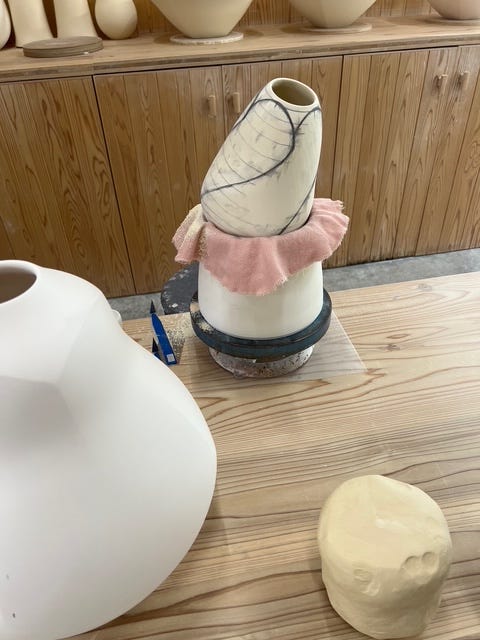

The most substantial and ambitious contribution of Akihiro Maeta to the story of Japanese kogei is turning white porcelain from its traditional role in tableware to a powerful property for contemporary art. Whereas Japanese porcelain has been characterized by embellished blue-and-white and colorful patterns, Maeta has given it a new and daring identity by stripping the white clay of all its typical adornments, revealing its purity and clarity. Under his hands, white porcelain has reached its ultimate and unpredictable expression and a remarkable minimalist aesthetic sensibility. While Maeta’s unadorned, flowless sculptures are inspired by the forms of vessels, the result is three-dimensional, abstracted, and faceted geometrical forms. They are refined and delicate, yet powerful and intriguing.

Maeta’s work is poetic and uplifting, immersing us deeply in the Japanese narrative and its aesthetic ideals. Yet, it is not the Japanese sense of beauty found in the imperfection that he manifests, but rather an ultimate perfection and subtle beauty. He has constructed an entire world in white, which has grown from the peaceful landscape surroundings of his coastal hometown, Tottori, known for its magical sand dunes. The change of seasons, the light, and the raw nature, the scenic coastline, and the surrounding Mount Daisen with its snowfall are all reflected in his art. Observing the snow closely, Maeta is intimately acquainted with its rich shades, in the colors affected by the light scattered and bounced off the ice crystals, the shadows, and the surfaces, constantly changing its color depending on the time of day and the landscape nearby. Maeta’s white porcelain embodies this notion, as it is not pure white, but has a distinctive shade that is difficult to describe—a secret recipe, if you will, much like the snow in nature.

Maeta is designated a ‘Living National Treasure,’ the highest award in Japanese crafts, bestowed upon those who have achieved the ultimate mastery of their craft. They are holders of intangible cultural properties recognized by the Japanese government as preservers of cultural heritage. Only a perfectionist like Maeta is capable of achieving minimalism as its ultimate representation by stripping away form to reveal its essence. He has devoted his life to exploring subtractions, the central value of his oeuvre.

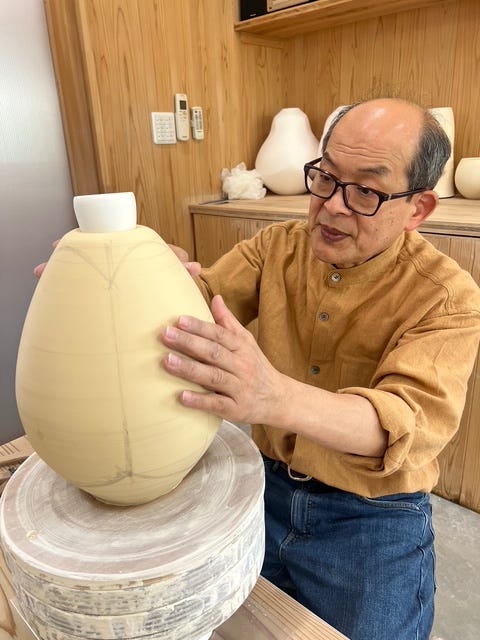

His method is surprising and unexpected. While his sculptures initially appear to be formed on a wheel, perhaps due to the reference to vessel shapes, they are, in fact, molded entirely by hand. When the clay is dry, Maeta begins sculpting the facets, using a single blade to remove material, as he approaches the final and most important phase of his work, just before applying the glaze. Maeta fires his sculptures in a low-temperature gas kiln next to the studio. His pieces are elegant and intriguing, with distinctive silky surfaces, smooth, soft, resembling the feel of Japanese silk. They are sensual and can hardly be fully appreciated in a photograph. It is the touch, the color, the feel, which brings them to life.

This visit was made possible by A Lighthouse called Kanata.