Towards a Nude Architecture

The Story of the Japanese Onsen

As a fan of Japanese culture and aesthetics, one of my favorite destinations while traveling there are the onsen—Japanese hot springs. They not only represent a significant aspect of the local culture and lifestyle, but they are also visually compelling and enrich the Japanese experience. And to me, they also symbolize the health and hygiene practices that are rooted within Japanese culture. Visiting an onsen makes you feel relaxed, healthy, and completely clean, and fall in love with water. They are typically situated in picturesque mountains, the breathtaking countryside, and in towns such as Beppu, the home of thousands of onsen which I have recently visited. However, the onsen is not to be confused with the sento, which is a public bathhouse where heated tap water is used. Learning the rules and etiquette for onsen bathing as well as the aesthetics and architecture attached to them is a rewarding path to becoming more familiar with Japanese culture. Now that architect Yuval Zohar has published his decade-long exploration into the Japanese onsen in his new book Towards a Nude Architecture (published by nai010), it is time to dive deep into this unique Japanese institution which he describes as “temples to steam and sweat.”

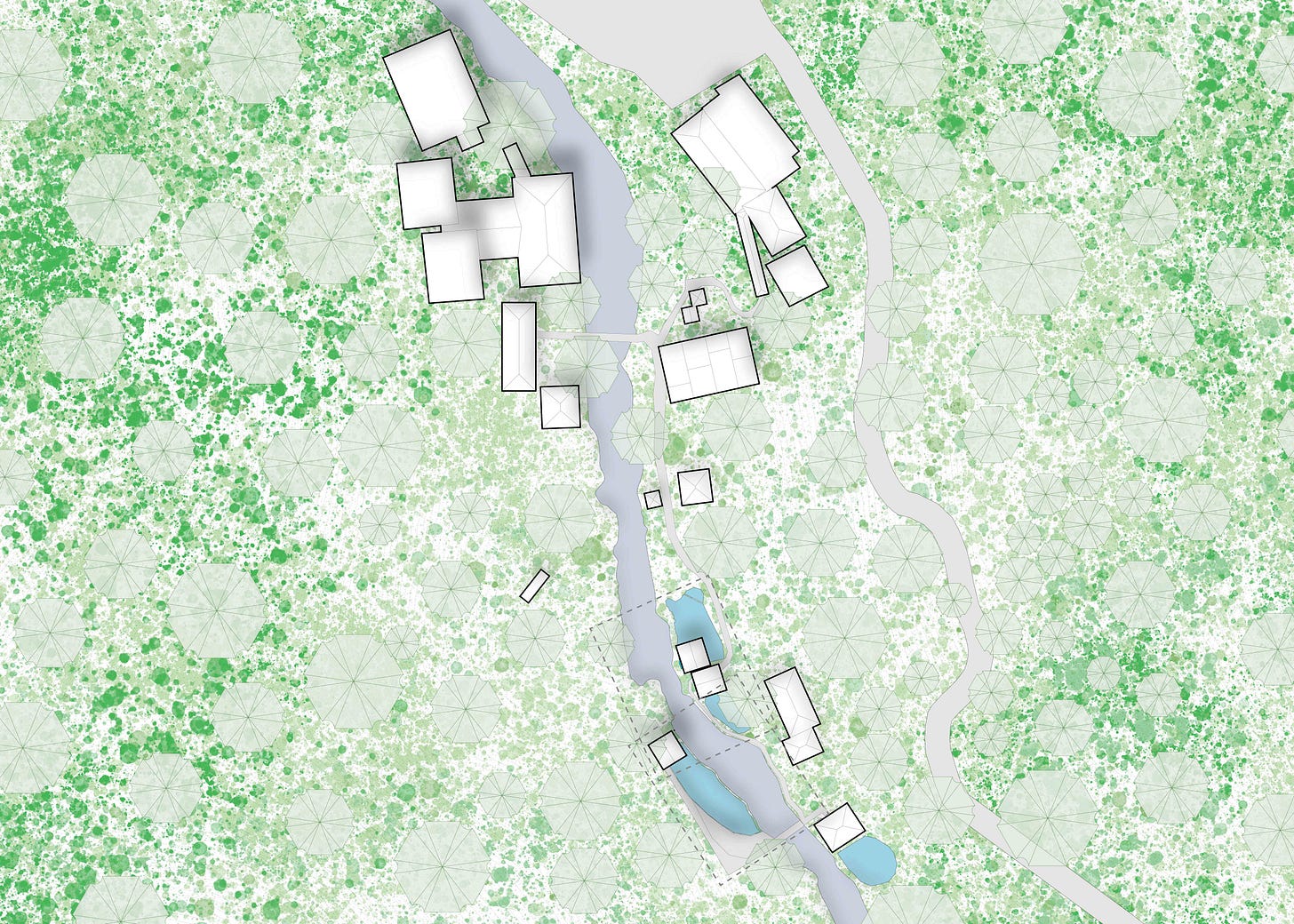

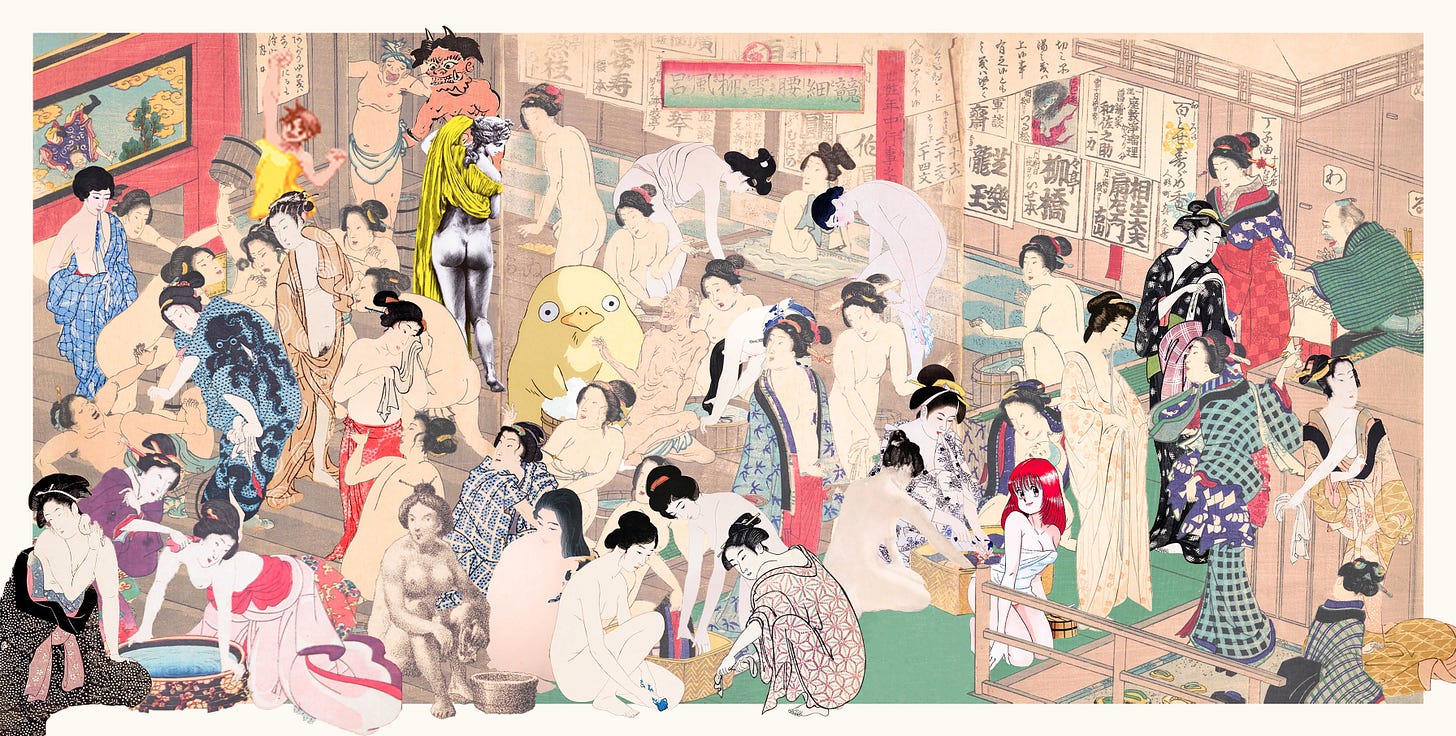

Zohar is an American architect who started his career with Diller Scofidio + Renfro and OMA and has lived and worked in Japan for years has an incredible sense of aesthetics. Currently, he is based in the onsen town of Yugawara in South-Central Japan, but developed a passion for the Japanese onsen even before moving to Japan. Zohar tells us that Japan has approximately 30,000 natural hot springs—more than any other country in the world—and his text is fascinating. It is illustrative with remarkable imagery that brings the reader into the experience of visiting an onsen. His book includes photographs, drawings, and diagrams, as well as imagery from history that brings the onsen to life while guiding his readers through a fascinating journey to this magical world of Japan’s hot springs. While a variety of aspects are discussed, the onsen are predominantly presented through a visual and architectural lens. The book is divided into three sections: past, present, and future, making the read clear and enjoyable.

Zohar identifies the richness of architectural expressions attached to each individualized onsen, presenting a symphony of styles that bring to life its sensuality and the culture of water. It is not only the architecture, colors, minerals, and beverages for which onsen water are utilized, but also the food cooked in the onsen and the artifacts attached to it—like buckets, stools, and baskets—which makes it into an integrated element of Japanese culture. Zohar selected onsen from various regions where the architecture, wood, and design styles are organic, reflecting the local landscape, revealing how they are harmonized with some magnificent places. Among the onsen featured are historic landmarks as well as contemporary ones. He found them located in towns, mountains, forests, and other locations, spanning four of Japan’s islands and demonstrating that the relationship to the locale is fundamental. I loved the inclusion of the House of Light, which captures the potential of the onsen to become a work of art in its own right—a masterpiece, designed by American artist James Turrell in 2000.

In the last chapter, devoted to the future of the onsen, Zohar becomes more emotional, poetic, and personal. He speaks about the declining custom due to the increase in privatization, leaving Zohar to question the future of both the onsen and the sento. In this gem publication, he advocates for saving these sanctuaries and their cultural need to be preserved.