The Birth of Art Deco

Rhulmann and the Hôtel du Collectionneur, 1925

When Jared Goss was a young curator at the Department of Modern Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he helped organize the 2004 seminal exhibition, ‘Ruhlmann: Genius of Art Deco,’ a traveling show which has since become a benchmark in the history of French design. Devoted to Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1879-1933), the leading furniture designer and decorator of the 1920s, that exhibition, in collaboration with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, marked a point of departure for Goss’s career. Today, an independent curator and scholar, he is considered a world-renowned expert on the French decorative arts of the Art Deco era. His contribution to the exhibition catalog – still one of the best publications on the subject – was an essay on the Hôtel du Collectionneur, the famed pavilion that the French decorator created for the 1925 Exposition, Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. It became the subject of his new publication, The Birth of Art Deco: Ruhlmann and the Hôtel du Collectionneur, 1925, published by Rizzoli.

Goss was my recent guest in ‘Masterpieces of Design and Architecture,’ as we celebrated his new publication, which marked the centenary of the 1925 Paris Exposition. “Ruhlmann’s pavilion,” he said on the iconic structure which existed for only six months, “represents perhaps the most complete and elegant expression of Art Deco taste, one of the significant aesthetic achievements of its age.” The 1925 Exposition, the most ambitious presentation of Art Deco in history, took place in the heart of Paris, spanning the area between the Esplanade des Invalides and the Grand Palais, and extending along both banks of the Seine. In a fascinating talk, Goss revealed the exact location of each pavilion. Sadly, none survived.

What is Art Deco? I inquired about the term, which was coined in the 1960s to abbreviate the name of the 1925 Exposition, Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, and which has since become increasingly opaque as scholarship has developed. “It is,” Goss announced, “among art history’s most ambiguous and imprecise terms. Art Deco is commonly (if indiscriminately) used to describe the decorative arts, architecture, and even fine arts produced internationally between the First and Second Wars.” According to his definition, it does not describe stylistic characters, but rather the period of the interwar years, encompassing a variety of visual expressions, created across the globe. Goss says that the finest, the purest, and the most remarkable expression of Art Deco happened in France, where it originated. Within the Parisian design landscape of the 1920s, Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann was the most noteworthy ensemblier of his generation. Unlike today’s interiors, which are composed of objects gathered from various sources, ensembliers at that time “designed and either manufactured or commissioned everything they needed for the desired effect.”

Goss’ book is devoted to one building, a sequence of the most luxurious interior spaces of the home of the idealized, semi-fictional collector, created by the Ruhlmann’s group. “Who was that collector?” I asked. It was, in fact, Ruhlmann himself who played the role of the collector, and it was his own taste that ultimately determined the visual direction of the pavilion. It was the most publicized and well-visited pavilion of the 1925 Paris Exposition, presenting the best of the new French style. Ruhlmann extracted his distinctive and personal luxurious vocabulary from the 18th-century Golden Age of French Decorative Arts.

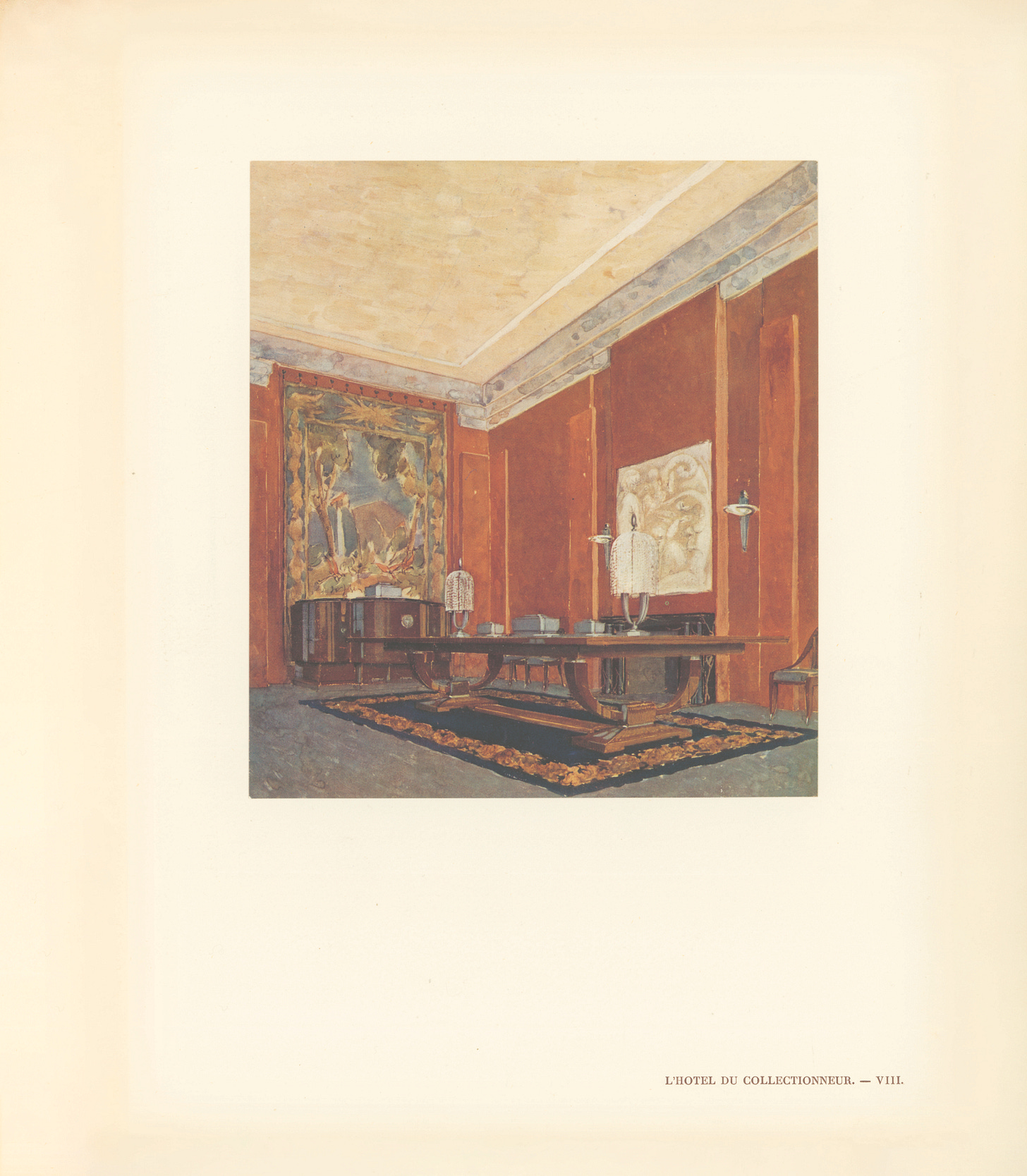

In a chapter that is mostly biographical, we learn that while he was a gifted draftsman, he was actually not a craftsman. “Ruhlmann’s work of the 1920s,” Goss suggests, “is considered his finest, embodying the combination of traditions and innovation that typify French Art Deco.” And his vision of spaces was summarized in his own words: “One room, one space,” he famously said, “cannot be considered in isolation.” It was the relationship between the rooms that mattered—the circulation that brought them together into one whole, into a symphony of abstract classicism, a concept embodied to its ultimate extent in his 1925 pavilion. “What makes this building great?” I asked. “The richness of the pavilion’s interior,” he said, “contrasted with the sobriety of its exterior. It represented Ruhlmann’s skill as an ensemblier, his ability to provide every aspect of an interior from architectural details and furniture to textiles, lighting, paintings, sculpture, and objects d’art.”

The book is comprehensive, and its narrative is built gradually, providing the background information that allows us to fully appreciate the greatness of Hôtel du Collectionneur. The chapters are not repetitive, and the descriptions are balanced with analytical text. It opens with an overview of Art Deco and the crucial role of the artisans in reviving the greatness of French decorative arts, illuminating the various sources of the time. The second chapter, ‘The 1925 Exposition,’ places it in the context of the culture of the world’s fairs, illustrated with some magnificent imagery of the pavilions presented at the fair. In the third chapter, Goss explores the prolific career and biography of E.J. Ruhlmann, which leads to the heart of the book, ‘The Collector’s House of 1925,’ whose structure was modeled on 18th-century pleasure pavilions. Notably, a hunting lodge was built in Versailles in 1750. This chapter is accompanied by a facsimile of the original catalogue, which documents the pavilion, allowing the reader to immerse himself in the period and ultimately experience not only the pavilion but also to understand what makes it one of the best interiors of the century. The talk with Jared Goss allowed the audience to delve into the world of Josephine Baker and the Golden Age of Jazz, the vibrant and chic lifestyle in Paris, the life of luxury, and the story of one man who inherited his father’s decorating business and brought luxury back to the cradle of taste.