Poetic Kogei

Masaaki Yonemoto's poetic Art Glass

Poetic Kogei

Among the most substantial achievements of contemporary kogei, which not only bring it to the heart of the contemporary art world, but also signify the ability to rethink traditions, is the transformation from the utilitarian to the poetic. By creating objects and sculptures in the mediums of the crafts—clay, glass, lacquer, bamboo, wood—which are fresh, surprising, and replete with narratives, the artists included in this chapter succeed in evoking an emotional reaction and an aesthetic experience on a level unknown in historical kogei. In the same way that poetry evokes stronger emotions than plain text, so too do the new Japanese crafts demonstrate an incredible and lasting impact. Whereas it is metaphors that convey deep meaning (or abstractions that capture experiences, spirituality, and emotions), the mediums of kogei—clay, glass, bamboo, fiber—powerfully transcend pure emotions.

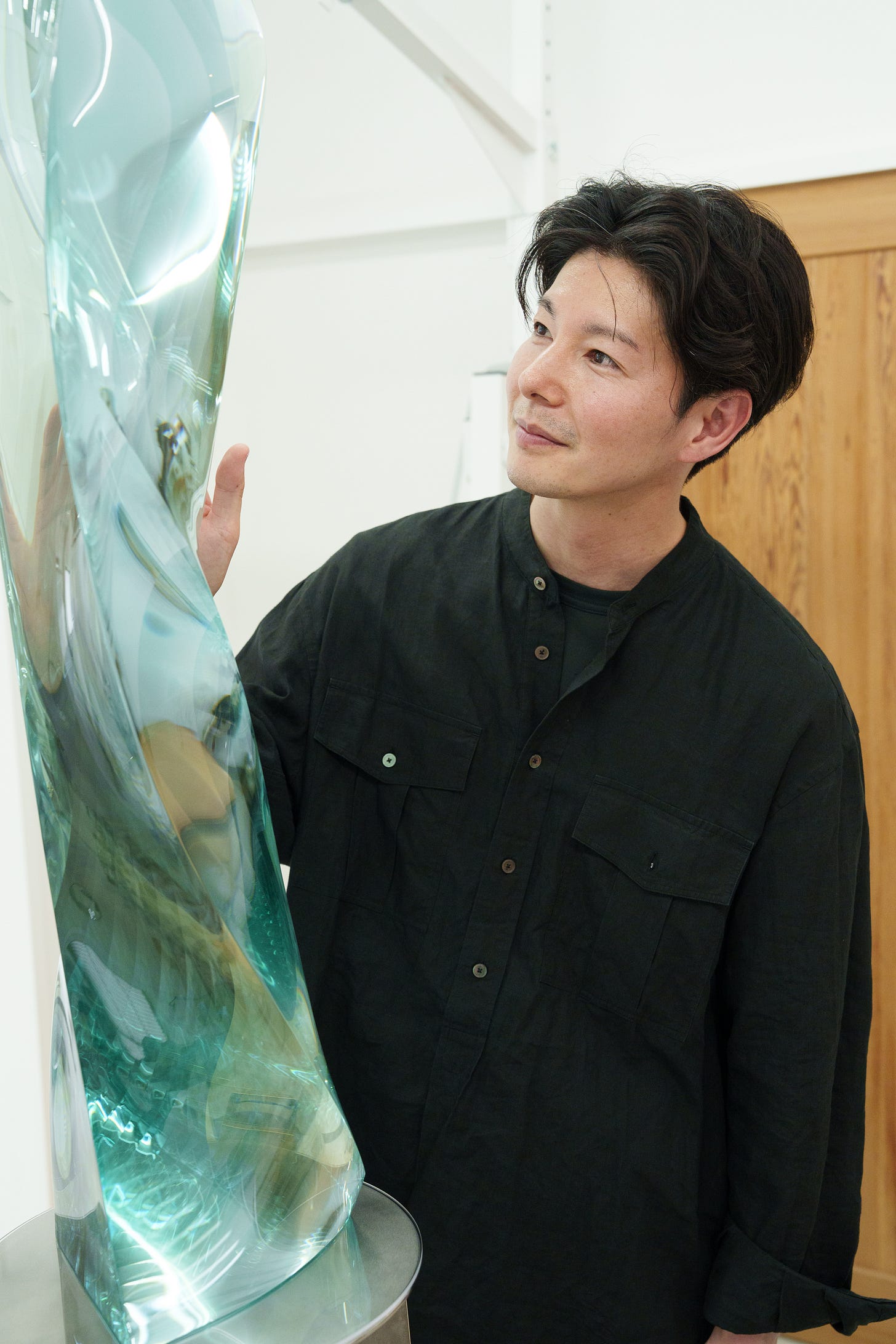

Masaaki Yonemoto (1987)

Masaaki Yonemoto belongs to a new generation of Japanese artists who create art glass, a medium without a long heritage or inherited traditions in Japan. To negotiate the relative newcomer medium with the Japanese narrative and to establish a strong connection have been the mission of those artists. For Yonemoto, it is about turning ordinary glass sheets—typically used in commercial construction using ordinary tools—into spectacular, fresh, and intriguing minimalist architectural sculptures. They manifest the Japanese narrative of harmony, peace, and perfection, as well as Buddhist spirituality.

I was introduced to Yonemoto’s work a few years ago when it was exhibited by his representing gallery, A Lighthouse called Kanata, and I was immediately moved by the unique expression of the material and by his futuristic, somewhat mysterious sculptures. They clearly evoked a sense of wonder and made me think of the all-glass architectural fantasies, beautifully and poetically described (but never realized) in a 1914 utopian novel by German author Paul Scheerbart, where a fictional architect travels the world by airship, designing fantastic glass skyscrapers. To Scheerbart’s generation of the German Expressionists, active around the First World War, clear glass spiritually transformed the world into a better place for a new and ideal society. I found that Yonemoto, too, perceives glass as an agent of change.

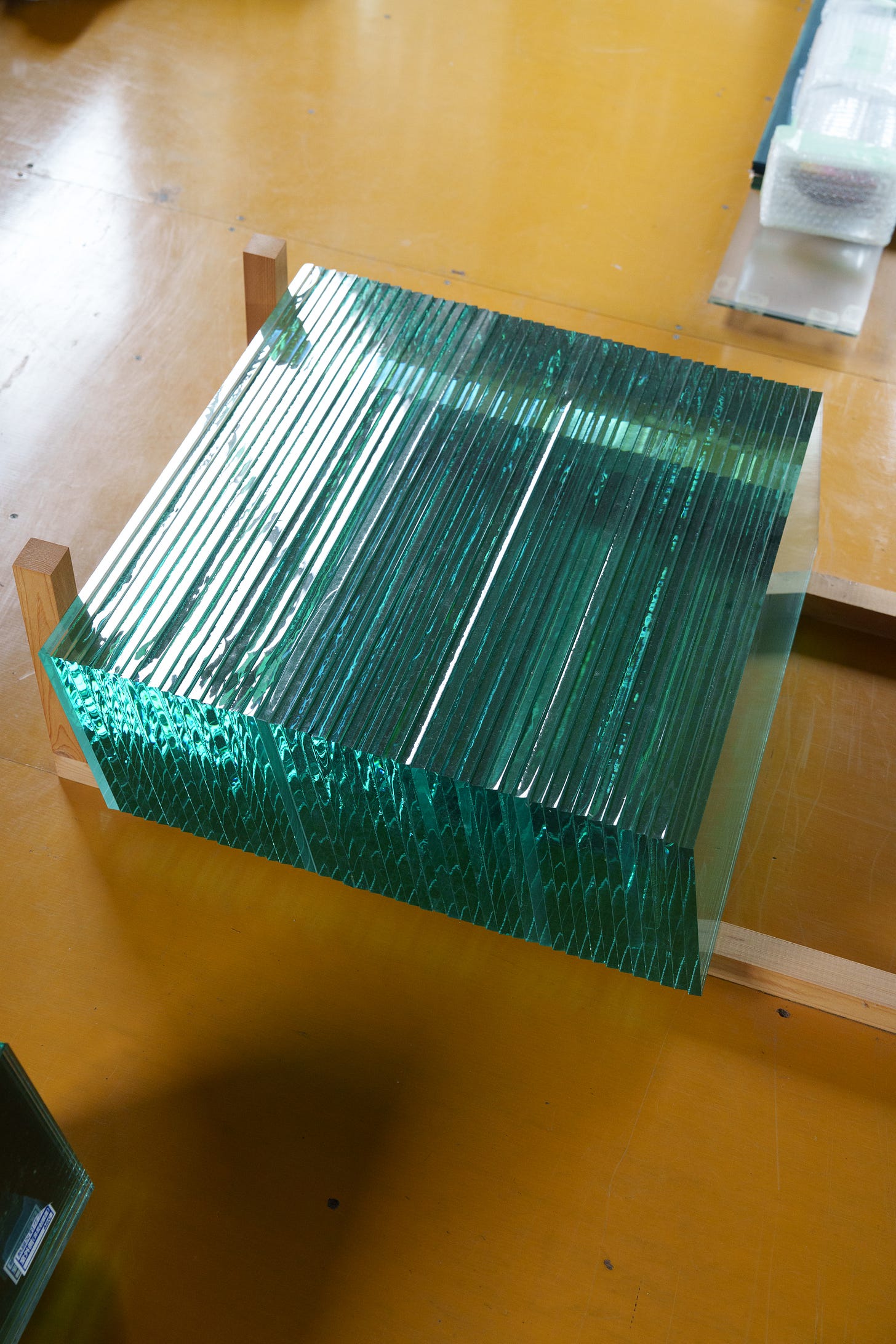

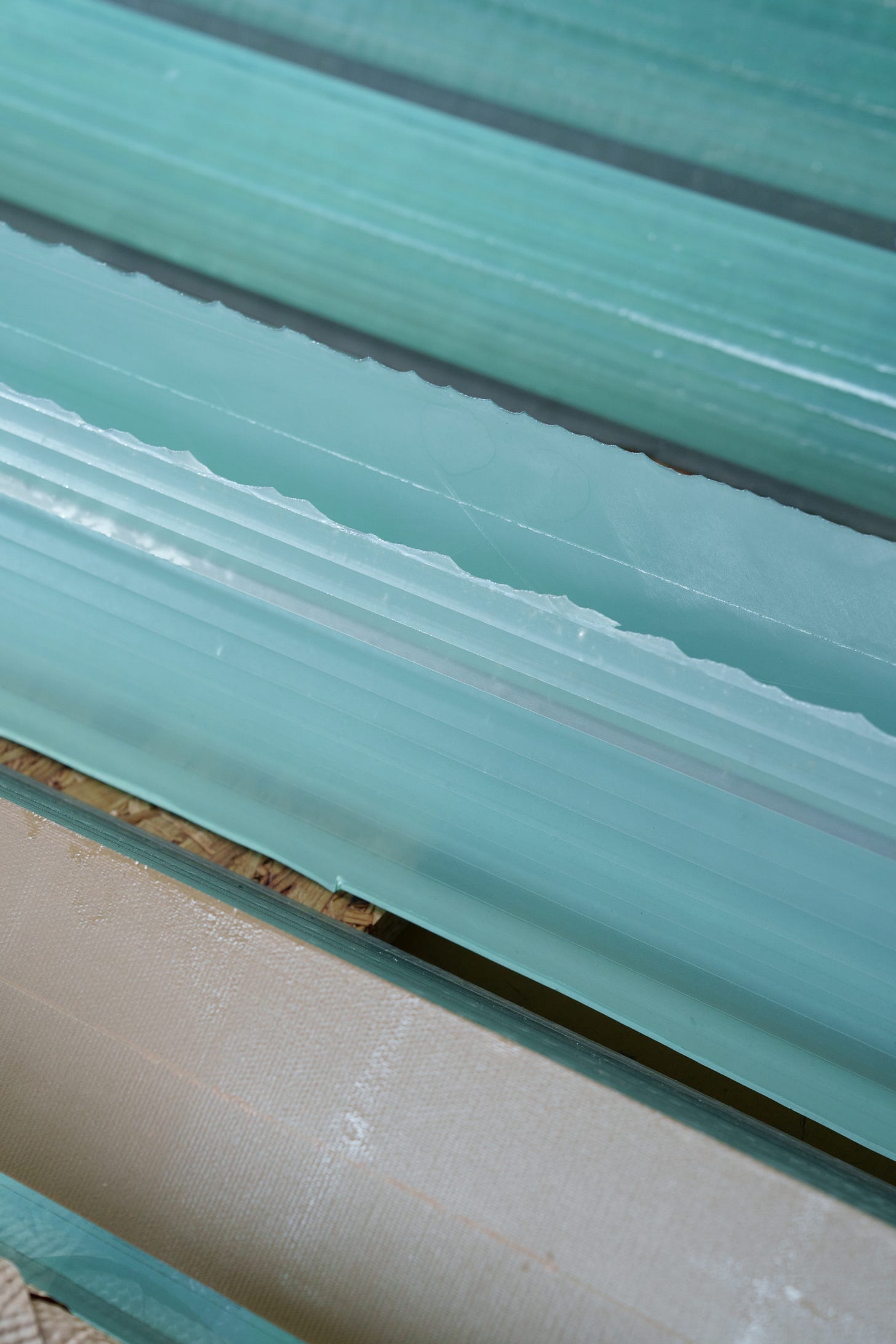

I must admit that Yonemoto’s work was somewhat enigmatic on all levels. While I thought at first that his sculptures were made from solid blocks of glass, perhaps cast, perhaps carved, it was clear that the highest level of gracefulness and elegance could not have been achieved in the cast technique. But more importantly, I had to understand the narrative of his oeuvre. When I recently visited his studio, situated in his birthplace town in Yamaguchi Prefecture, observed him at work, and listened to his story, I realized that he uses the glass lamination technique in his own extremely challenging way. Yonemoto’s studio looks like a laboratory in a science fiction film, a pristine, minimalist space equipped with unusual devices and tools, all meticulously organized. The second floor, at the top of a long stairway, is his storage area. There, he stores his raw material: thousands and thousands of glass sheets, organized by size, thickness, shape and color. The entire space looks like an art installation on its own. But there is also a great deal of spirituality present in the process.

He perceives his work as a manifestation of the aesthetic and moral values that have been a strong aspect of his identity, rooted in Buddhism and Zen. It is through his artistic work that Yonemoto finds joy and self-improvement. Just like for the German Expressionists, the glass to him transcends the physical material, and is rather a vehicle to achieve freedom and inner peace in the Buddhist manner, or as he puts it, ‘The feeling of my body and the glass melting into each other. Polishing the glass is truly meditative, and I would be delighted if by continuing this daily routine I can come even a little closer to the depths of the universal truth.’ I can see in his pieces the trace of Japanese ceramicist Fukami Sueharu, whose work he finds mostly influential, for the spiritual approach to the purity of material and form. The manner by which he successfully transforms that inspiration into something uniquely his own, developing his own voice, is refreshing to see.

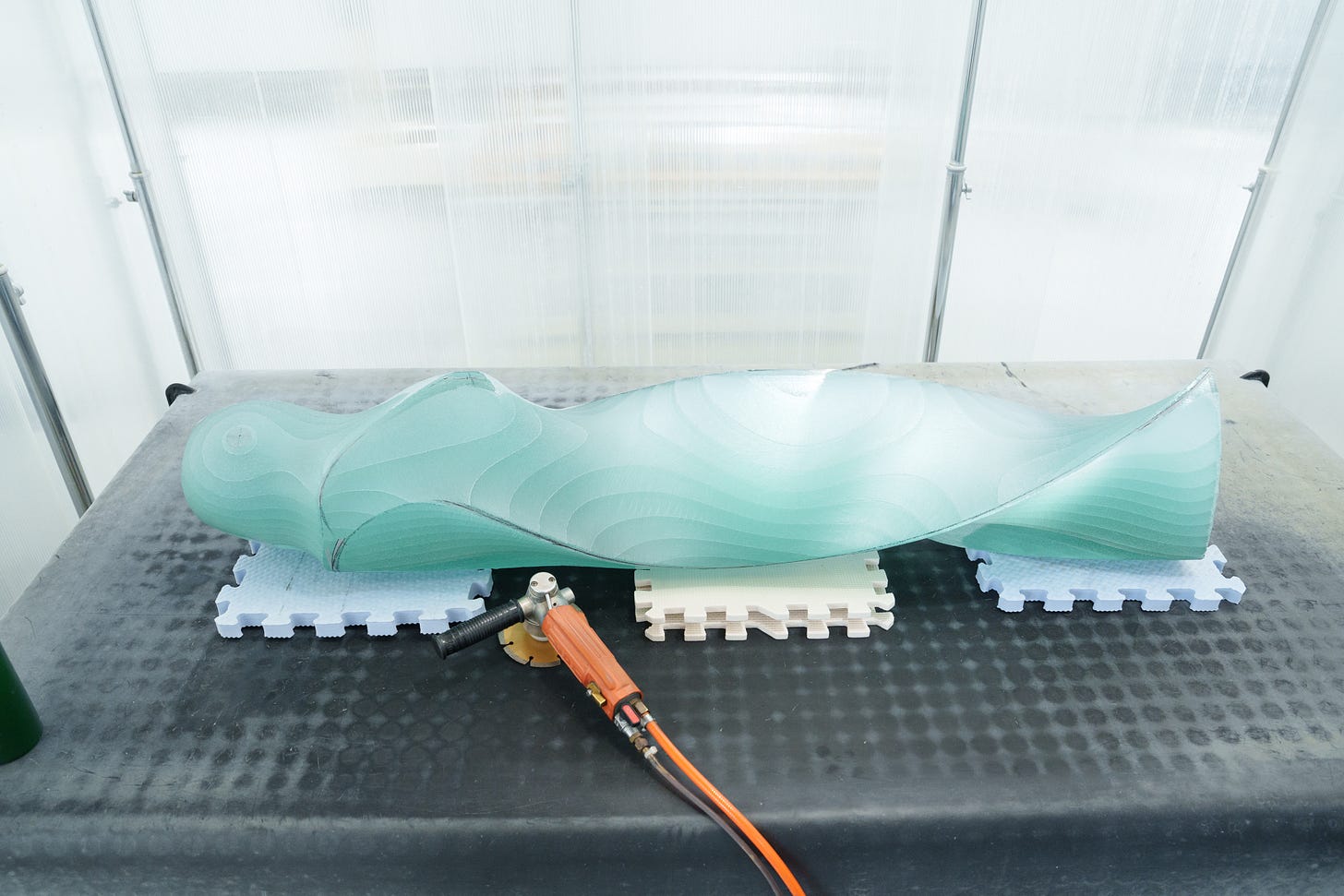

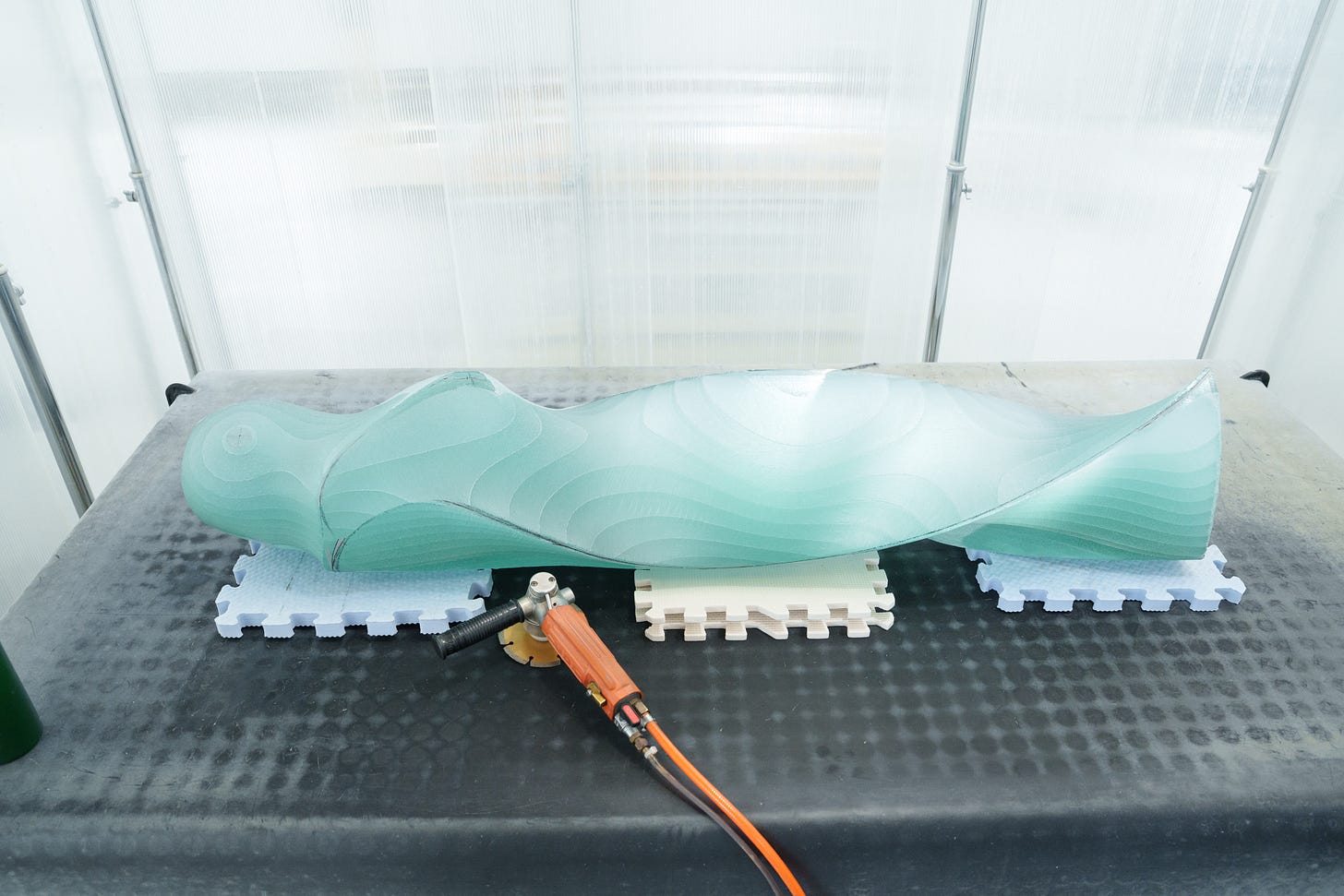

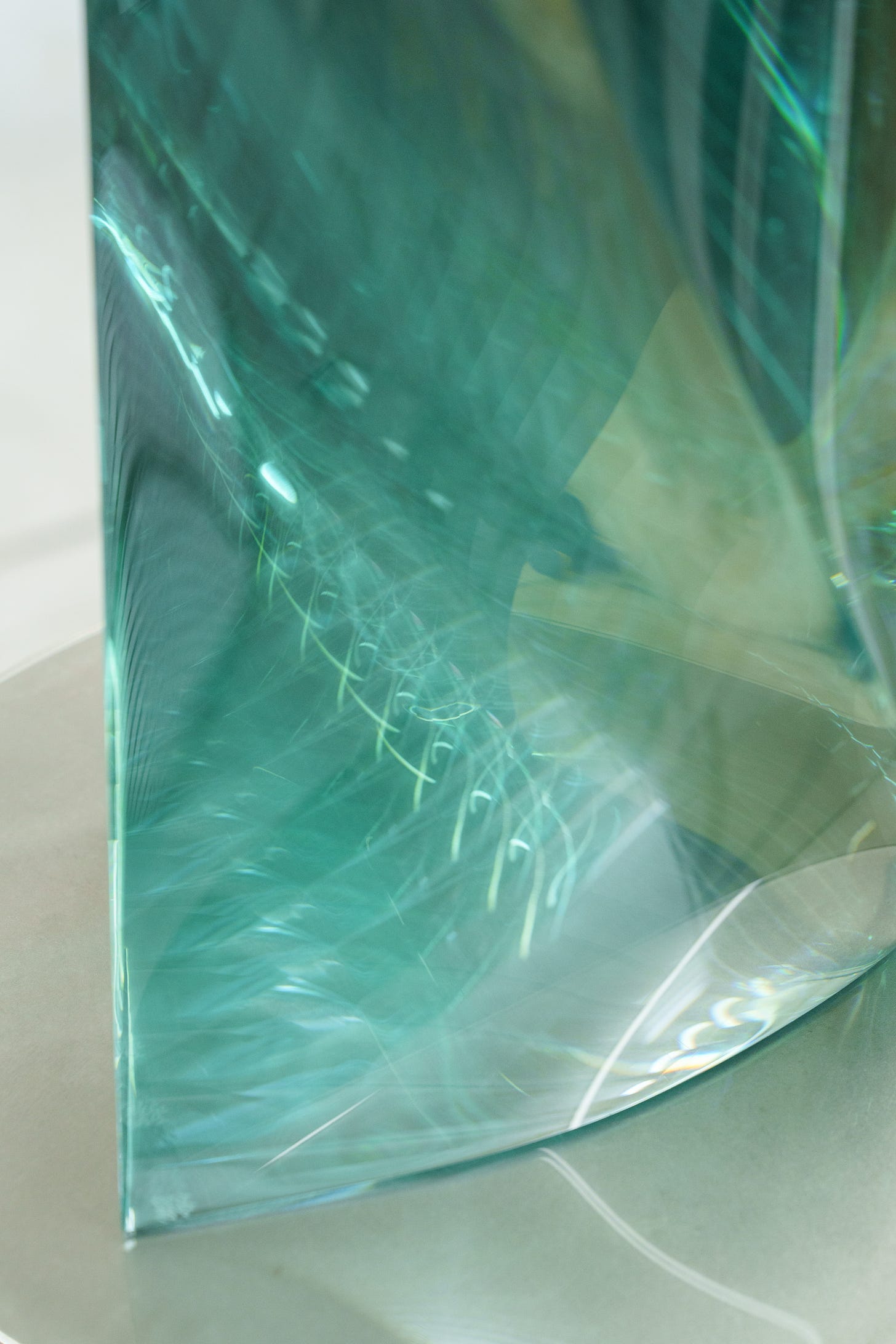

Yonemoto looks like a Japanese prince—elegant, refined, and graceful beyond words. He graduated from the Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts where he was first introduced to the art of glass lamination, before completing his graduate studies at the Toyama City Institute of Glass Art, where he met his glass-artist wife. He graduated in 2012, and it is astonishing that at 38, only twelve years after founding his own studio, he has mastered his extremely challenging and dangerous process. It takes the highest level of understanding of the material to obtain the skills required to achieve the level of his work, of which every phase is equally artistic and creative. Laminating layers of sheets glass by UV adhesive to bond glass to glass is a long and labor-intensive process, and takes a skilled hand to achieve a seamless connection and to avoid air bubbles. In his innovative way, he places sheets of glass coated in mirror between the layers to make his sculptures iridescent. Sculpting and carving the laminated glass into forms using diamond-head polishers is another creative and intuitive phase which allows him to achieve his exquisite forms. Lastly, he makes use of oxides in the polishing, ensuring that the work shines without damaging or causing cracks to the edges, and enhancing the beauty of the glass.

In his sculptures, each made from up to 20 sheets of glass, Yonemoto is celebrating the glass as a material for contemporary art in the most exquisite and personal way. His all-glass sculptures are pure and flawless, balanced without a base. They shine in the sunlight, showcasing the luminous green glass as it changes when seen from different angles. They look like skyscrapers at night in the fictional metropolis and there is nothing decorative or provocative about them. They are simply pristine, streamlined light towers; places of enlightenment.

Photography by © Takuro Kawamoto.

This visit was made possible by A Lighthouse called Kanata.