Japan’s New Craftspeople: Fumie Sasai

The Avant-Garde Lacquerware

Lacquer is a natural and transparent resin, a sap harvested from the Urushi trees, and used to create decorative objects by applying coats onto surfaces in multiple layers. The Asian craft has a long history, dating back to ancient times. Since lacquerware began to make its way to the West in the 16th century, it has captured the imagination of Europeans, becoming celebrated artifacts and symbols of status and taste, praised for their unique, soft-polished sheen and special ornamentation. Since the 1960s, lacquer has been reinterpreted by artists in Japan, who have been pushing the boundaries of the craft to new horizons, transforming lacquerware from traditional sacred objects, Buddhist altars, and shrines—as well as tableware decorated with gold powder—into abstract sculptures.

The new generation of craftspeople, following the footsteps of Kanazawa-based legendary artist Nobuyuki Tanaka, considered Japan’s most prolific lacquer artist, have utilized the unique substance and the traditional method of the craft to create contemporary and abstract sculptures. They use kanshitsu, the so-called Dry Lacquer technique, where the sap is applied onto hemp fabric, which covers a sculptural form that can be removed once the sculpture is complete, resulting in a pure representation of the material. In my recent expedition to Japan, I visited the studios of two lacquer artists, both women, who live and work in Kyoto. Both have achieved a personal language while modifying and contributing to the ancient process in their own voices. I was surprised to learn that lacquer art is practiced today primarily by women, and that approximately 80% of students choosing to major in Urushi-lacquering in Japanese universities are women.

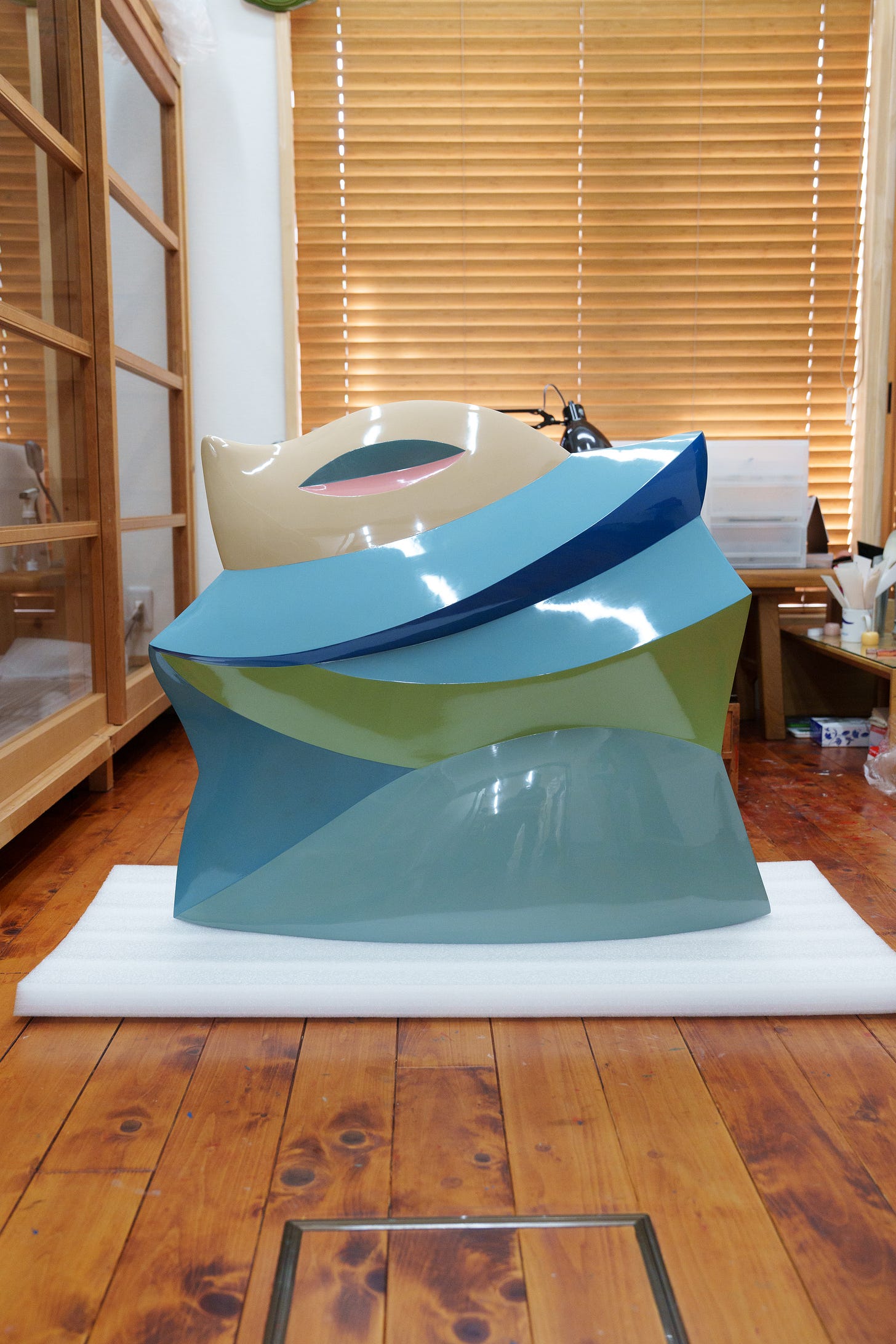

Sasai Fumie is a lacquer artist who synthesizes the traditional craft with contemporary artistic expressions and innovative techniques. She knows the history of Urushi lacquer and has gained tremendous experience through research, skill, and applying her formidable expertise. She has been successful in mixing pigments and creating lacquer in a variety of vibrant and unusual colors for the material. Her forms are organic, sleek, and abstract, with a strong sense of minimalism. It is the method of removing the mold that enables her to achieve that quality of forms (rather than the method that keeps the wooden mold inside the finished sculpture). They are largely derived from flowers and seeds and from animals, all manifested in abstract sensibilities. She is one of the rising talents in lacquer, and her work has been exhibited internationally.

Fumie studied with master craftsman Shinkai Gyokuho at the Department of Crafts at the Kyoto City University of Arts, from which she graduated in 1996 and where she is a current faculty member. While she intended to study ceramics, she told me that her second year, when students were encouraged to choose their major, she instead chose Urushi-lacquering, because, she said, of the way it suited her sensibilities. Gyokuho was a pioneer in creating non-functional objects in dry lacquer on a Styrofoam core, beginning in the 1960s. From him, she learned abstraction and the use of Styrofoam as the base material on which to apply the lacquer.

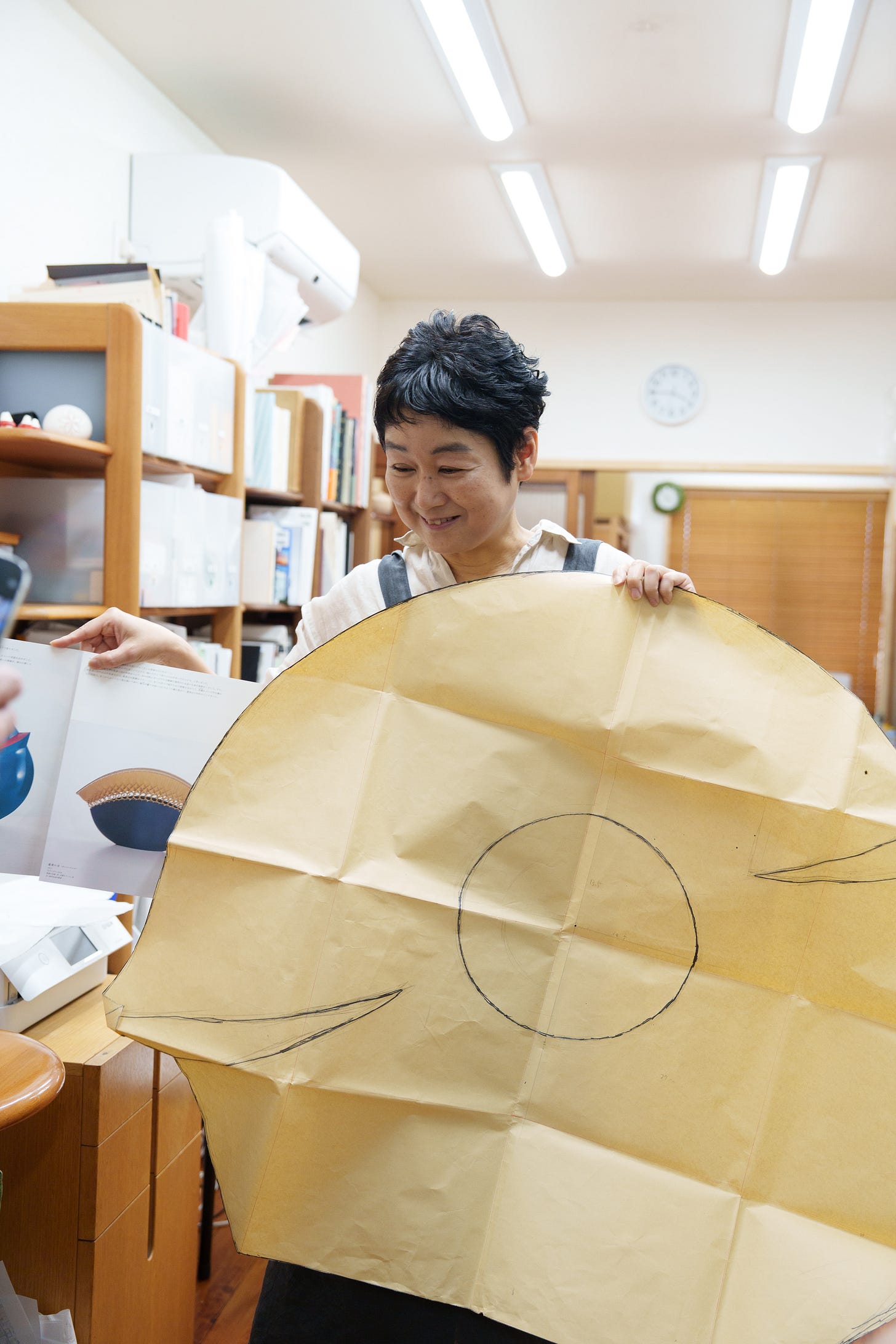

Visiting her studio in the suburbs of Kyoto was rewarding, as Fumie demonstrated her technique while speaking about her passion for the material and for her artistic expression. She starts with creating the core forms of her sculptures by cutting and shaping a block of very hard Styrofoam. She then makes drawings directly on the Styrofoam, outlining the form by freehand. At the end of the process, the Styrofoam will not remain inside the sculpture, as it is used as a temporary mold, allowing the artist the freedom to achieve any form she wishes and to abstract nature in her own voice. She then smooths the surface using various grades of sandpaper, as the last shaping of the Styrofoam is crucial in making the sculpture perfectly sleek. When the form is ready for applying lacquer, she pastes the sculpture with hemp fabric, using an organic glue, which consists of a mix of lacquer and rice powder. Now she begins applying multiple thin layers of Urushi lacquer, one after the other—up to 30 layers. Each coat has to dry before the next is applied. At the end of the process, she achieves a hard substance in a variety of colors, and the Styrofoam is ready to be removed. She achieves hollow, light, three-dimensional, and organic sculptures in pure lacquer. Lacquer is hard to communicate and describe in words or in photography because the reflective surfaces, the luster, and the softness really must be experienced firsthand. This uniqueness cannot be emulated, bringing an Eastern flavor to contemporary art.

Photography by © Takuro Kawamoto.

This visit was made possible by Sokyo Gallery.

Did you visit Kintsugi artist studio in Yamanaka Onsen? He was introduced by NHK. Very popular Kintsugi originally lacquerware craft.