Gio Ponti: More than One

Conversation with Manfredo di Robilant

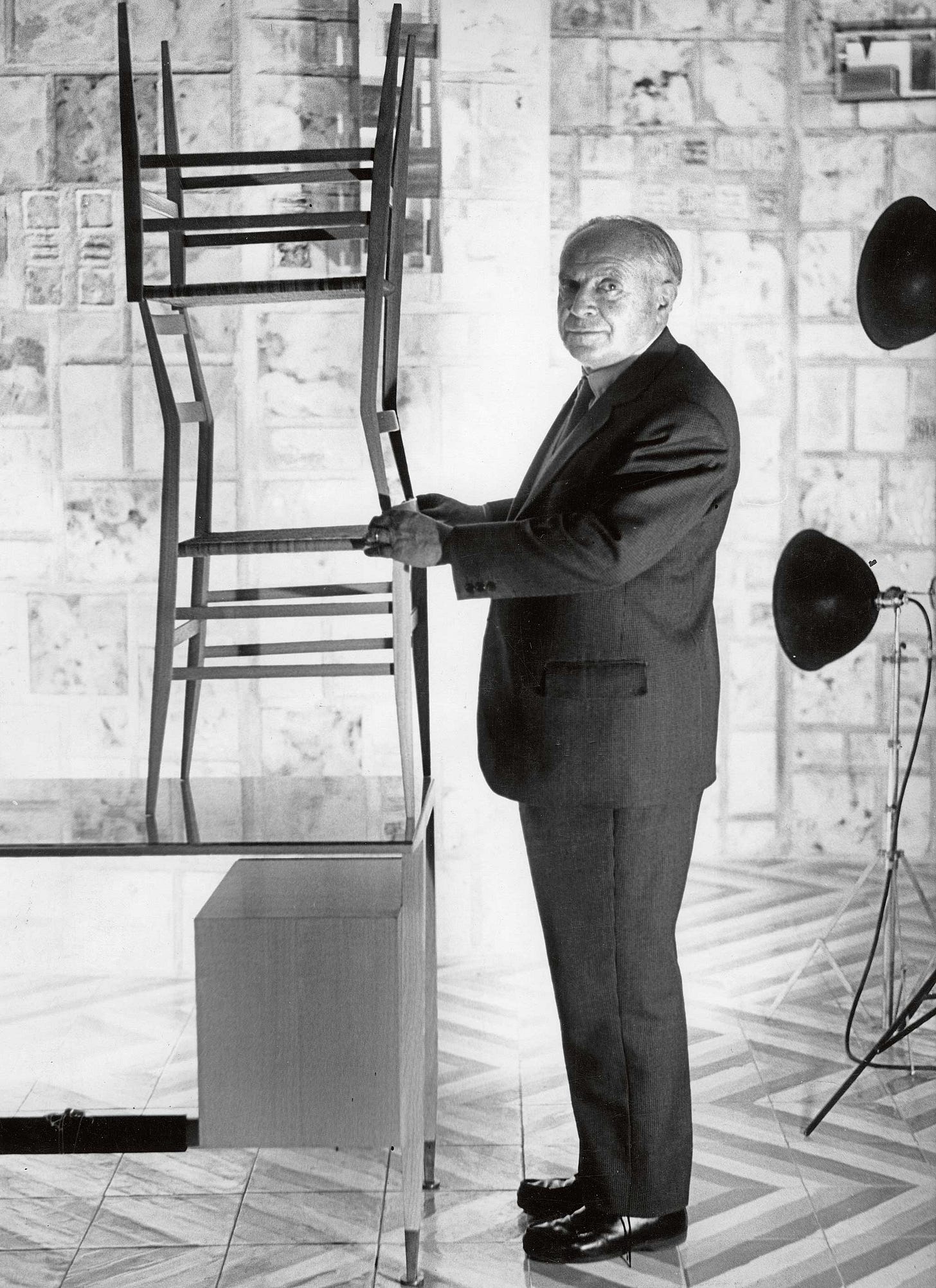

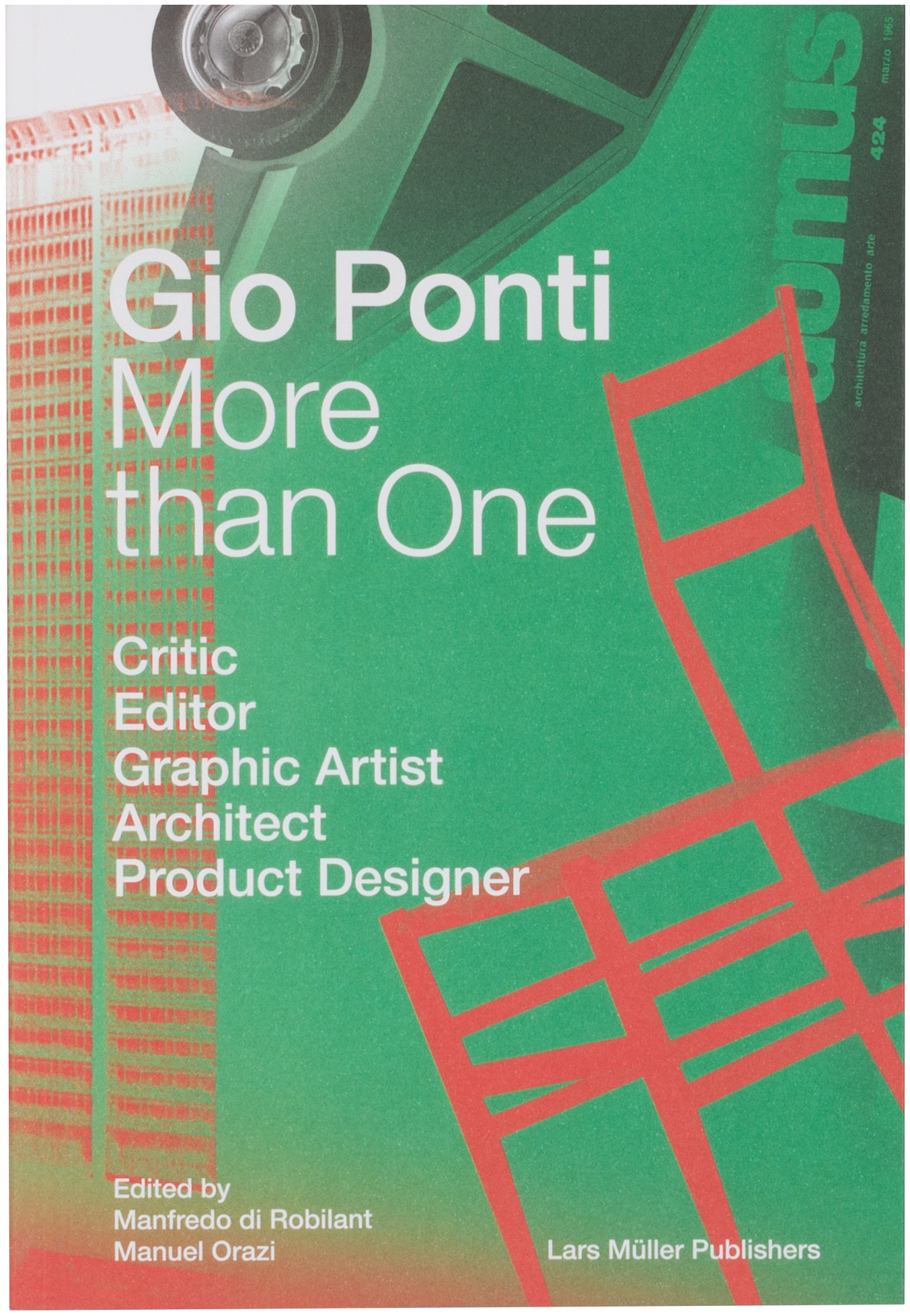

The heroic legend, Gio Ponti (1891-1979), has typically been portrayed as the ‘Godfather of Modern Italian Design,’ who brought international recognition to Italian design during the country’s economic boom of the postwar years. He was a mega talent who successfully infused modernism with Italian traditional craftsmanship. A new book, titled Gio Ponti: More than One, Critic, Editor, Graphic Artist, Architect, Product Designer, brings to light the legacy of the real Ponti (known familiarly as Gio) who was at times controversial; at times behind or against the curve; not always rational and practical; sometimes disconnected with the Zeitgeist; and often sat on the fence as while having a relationship with Mussolini, never directly aligning design and architecture with the Fascist regime. The new volume, published by Lars Muller, a collection of essays by scholars on selected topics from Ponti’s six-decade career, reveals the stories behind the oeuvre of the Milanese architect, designer, and founder of Domus. The title alludes to his range of skills across fields, but also reveals that although Ponti created graphics, was active in urban planning, and published books and endless essays. It was his design of products and decorative arts that his genius was primarily expressed, and where he ultimately fortified his contribution to the story of modern design.

Co-editor of the book, Turin-based architect and architecture historian Manfredo di Robilant, was my recent guest in ‘Design and Architecture Masterpieces.’ We explored the meteoric rise of Ponti’s career during the Italian Economic Miracle, the development of his mature style, some of his guiding principles, and the years of his decline. “The book,” he says, “comes to illuminate all of Ponti’s multiple portraits and overlapping careers – writer, editor, product designer, and an architect.”

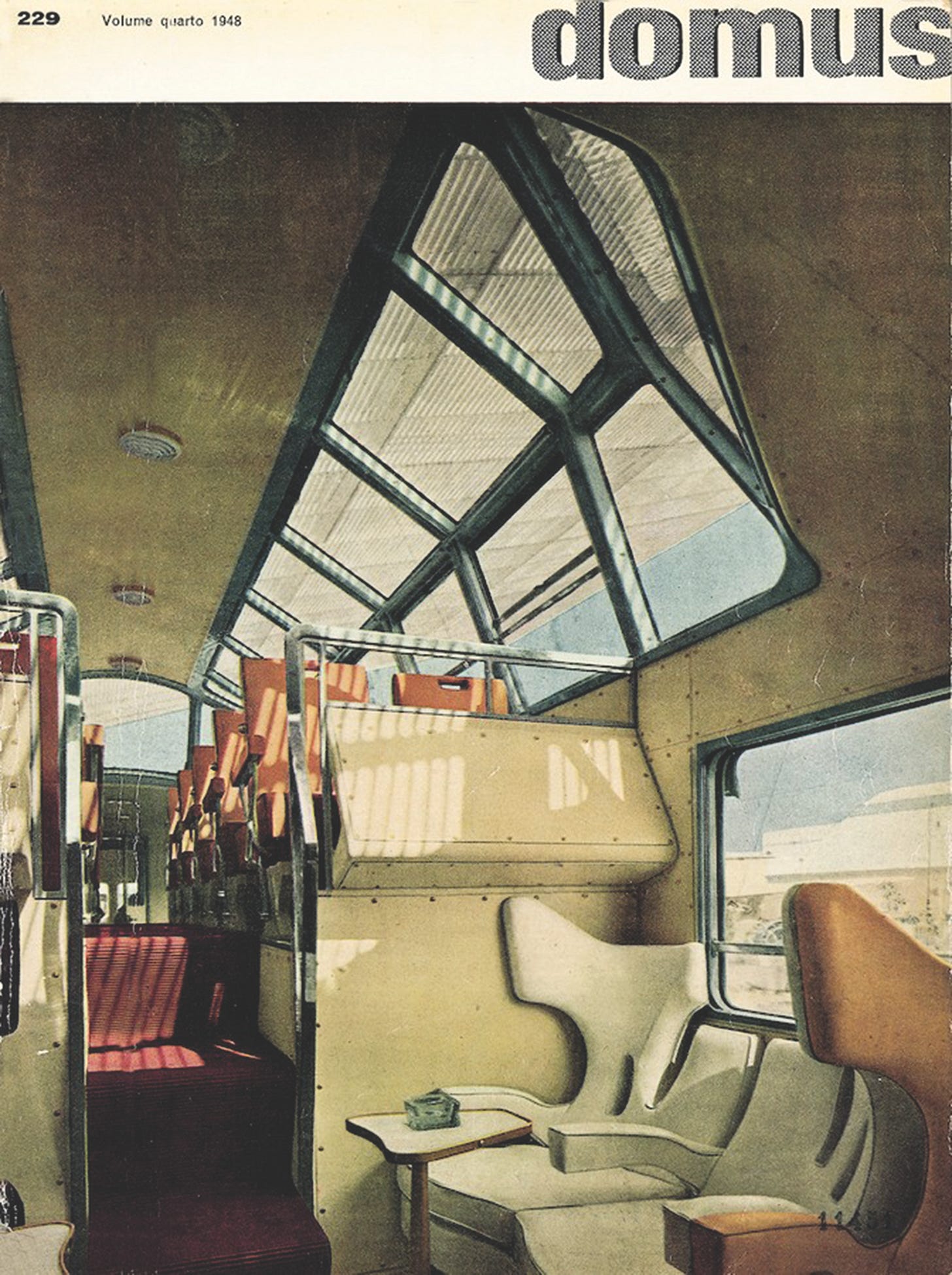

Like many of his mid-century contemporaries, Ponti was aware of mass media’s power during the “golden age” of Italian advertising, when products were brought into Italian households through stylish ads. Ponti utilized the media like a magician. It served as an engine to enhance his career, communicate his ideas, increase visibility, solidify his distinctive visual vocabulary as ‘Italian,’ and capture the public’s imagination. Working for progressive companies that sought to improve public taste through advertising, such as Richard Ginori, Cassoma, and Pirelli, and founding Domus Magazine in 1928, brought Ponti to the intersection of media and modernity. Subsequently, everything he designed possessed a glamorous allure.

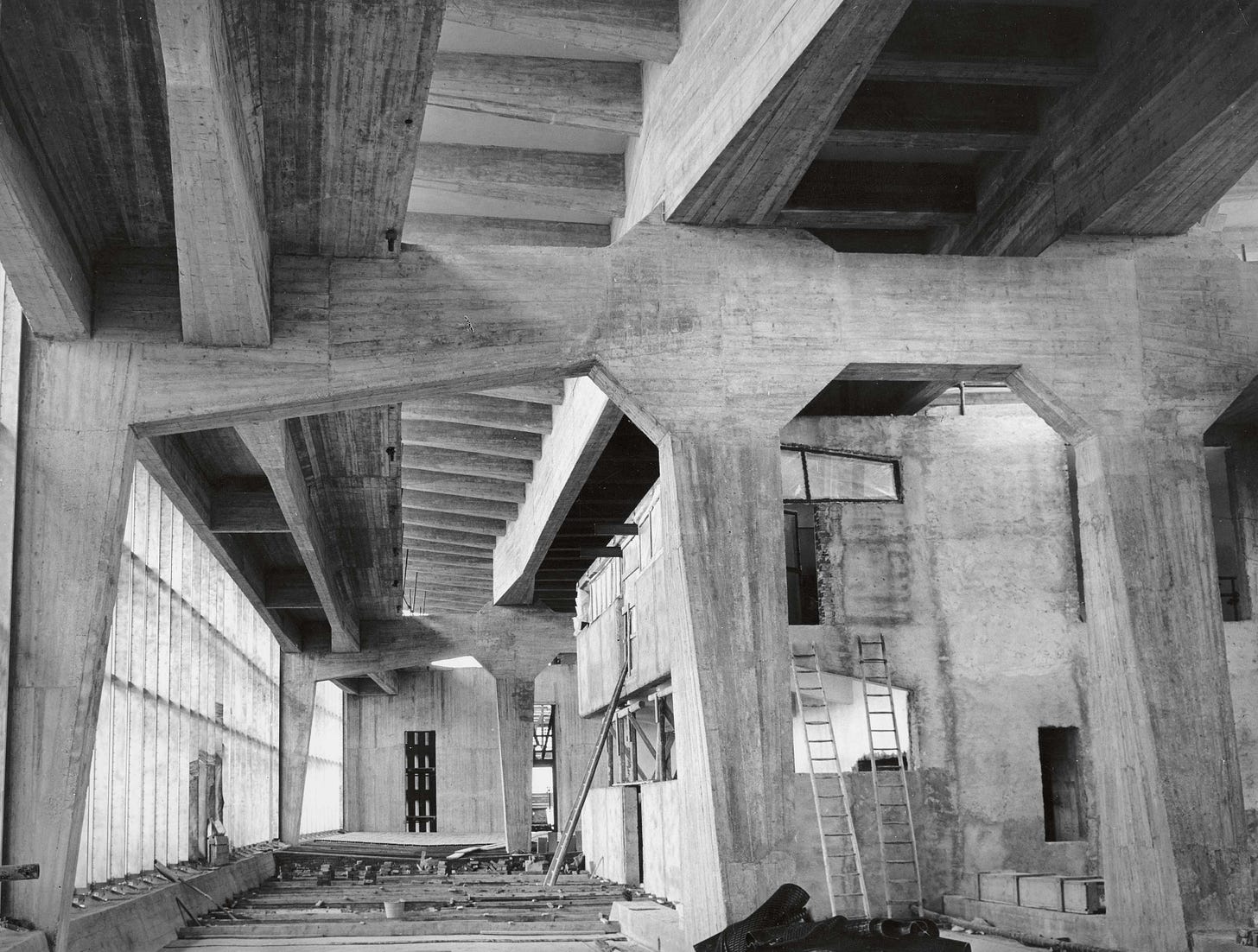

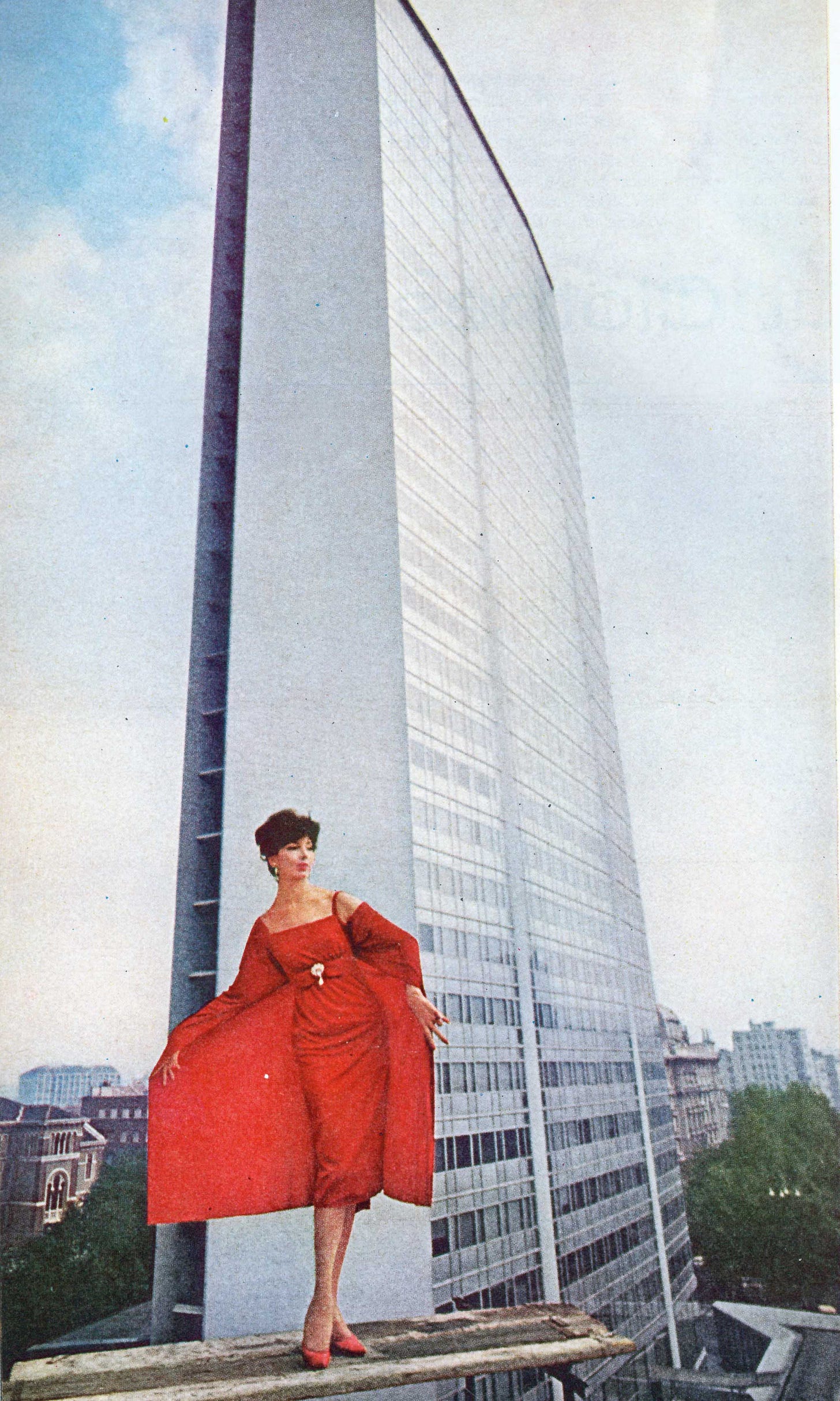

The book is divided into three categories – Writing and Graphic Art; Architecture; and Product Design – covering the entire scope of Ponti’s oeuvre, while examining a selection of topics. The section on architecture. which was my favorite, is devoted to two groundbreaking and iconic Milanese buildings – the Montecatini Headquarters of the 1930s and the Pirelli Tower of the early 1960s, which was Italy’s tallest building until 1995, symbolizing its recovery from the devastation and destruction of World War II. “Today, architecture,” Ponti said when working on the Pirelli, “is moving from the use of materials that were affected by and competed with time, toward the use of materials that are incorruptible, like stainless steel, glass, porcelain stoneware, and plastic—materials born of technology and not nature, materials that do not age.” The chapter ‘A Visual Atlas of Buildings by Gio Ponti,’ features Ponti’s portfolio of buildings, illustrated chronologically, allowing the reader to follow the path of his evolution as an architect from his first realized building—a House in Via Randaccio in Milan of 1926 – to his later architecture of the 70s in Denver, Hong Kong, and Singapore, demonstrating that Ponti always subscribed to the principles of the Modern Movement, yet successfully infused it with elements created by Italian crafts, particularly ceramics.

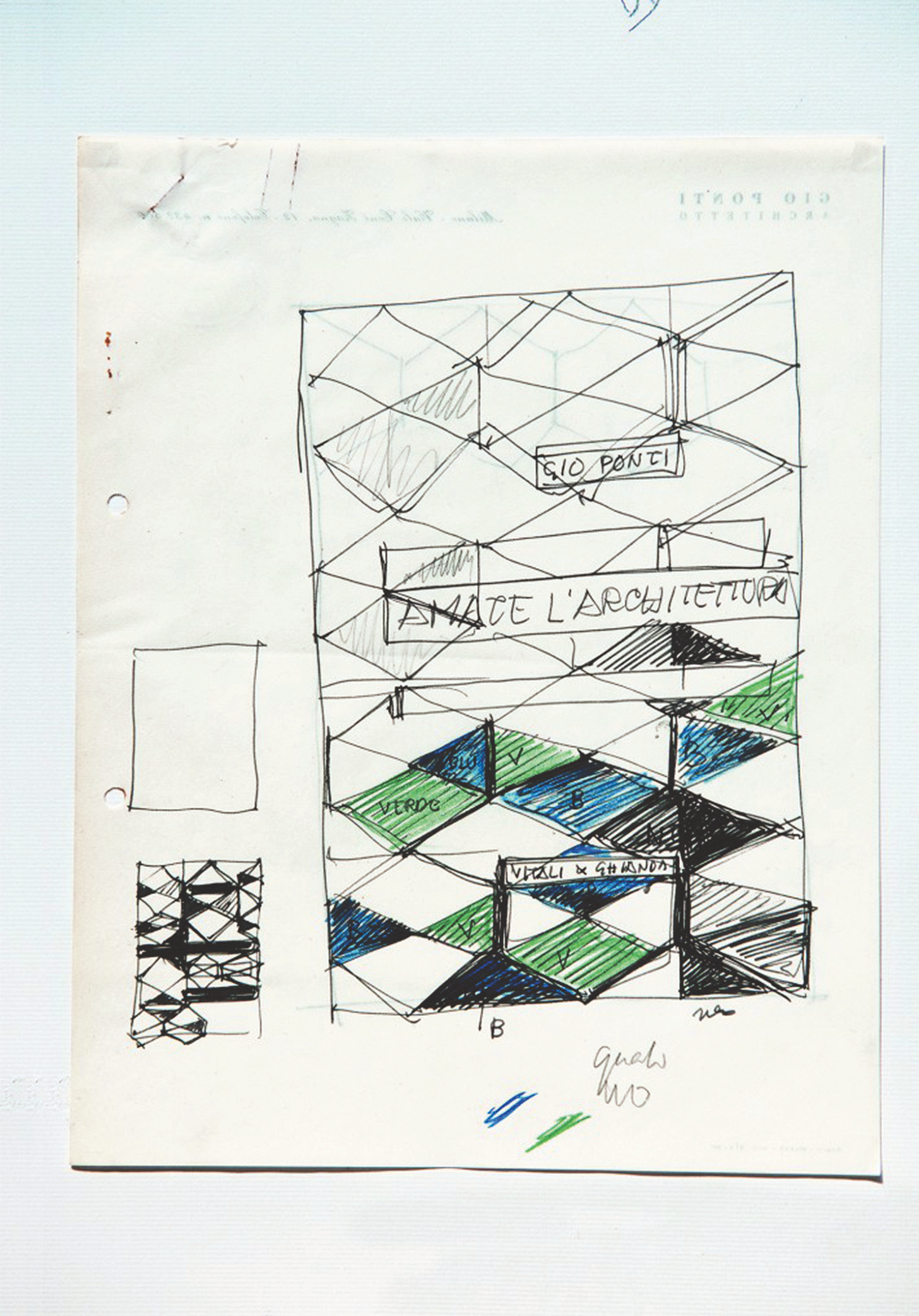

We learn that Ponti’s emblem—the diamond or crystal found in much of his designs in the postwar period—is related to his belief in ‘closed’ architecture, meaning that it should not be created as an organic entity with a potential for change or expansion in the future. That architecture should be a final product. Starting in 1945, when he published his first book L’architettura e un cristallo (Architecture is a Crystal), later published in a revised edition under the title Amate l’Architettura, Ponti explored and developed the theme of the crystal as the embodiment of the highest aesthetic values, the manifestation of the perfect ‘closed’ form. For German Expressionists, the crystal symbolized purity and social renewal post-WWI, which they expressed in their futuristic glass projects. In contrast, for Ponti, the crystal had become his signature emblem, which framed his style and philosophy. The Pirelli Tower, completed in 1958, was the ultimate expression of that idea, an urban-scale object that ought never to be changed or altered.

Another principle illuminated here was Ponti’s belief that architecture should not remain on paper, but that architects should design buildings to be built. This principle contributed to his fall in the late 60s, with the rise of the Italian Radical Design Movement and its dreams of a future with no buildings, as was famously advanced by the left-wing members of Superstudio, when reacting against the uniformity of modern architecture of the type Ponti created. When Italy was brought to the world’s stage in the exhibition ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape,’ which opened in May of 1972 at MoMA and curated by Emilio Ambasz, Ponti was excluded because his agenda was no longer relevant.

This book examines the multifaceted contributions of Ponti to the 20th century, tracing his enduring influence both in Italy and globally, through the lens of case studies. Unlike other publications on Gio Ponti, it examines in depth each of the principal facets of his activity through rigorously researched essays that draw on previously unexplored sources. Each essay offers a focused look that enriches and complicates our understanding of Ponti’s work, while bringing to the readers his buildings, his objects, and his interiors, which were always sexy, stylish, chic, so Italian, and always inpiring.