Frank Lloyd Wright

The Definitive Monograph by Robert McCarter

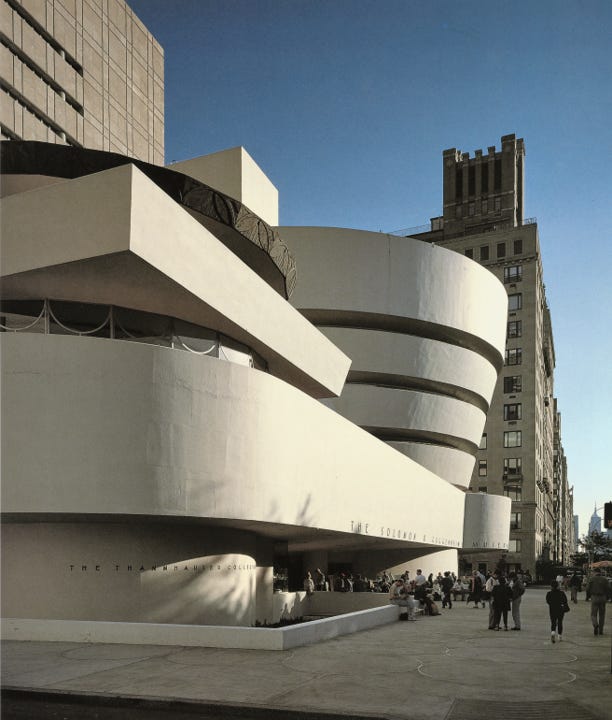

How can the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, the most famous architect of modern times—an American icon who designed over 1,000 buildings, completing nearly 600 of them—be boiled down into one comprehensive volume? Robert McCarter, a practicing architect, author, critic, and professor of architecture at Washington University, has accomplished just that. A lot has happened to Wright’s buildings since McCarter published his definitive monograph on the American architect in 1997: restorations, expansions, new discoveries, and countless documentaries, books, articles, and exhibitions. Wright’s buildings, some of which were built over a century ago, are living organisms that still evolve and draw tremendous interest. Now, McCarter has published the second revised edition of the monograph Frank Lloyd Wright, addressing recent changes in Wright’s buildings, such as the newly restored wings of the Darwin Martin House, which were furnished with reproductions of built-in furniture and stained-glass windows. Additionally, houses not included in the first edition have been added. McCarter was my guest in ‘Masterpieces of Design and Architecture,’ in which we celebrated the evolution of the private house in Wright’s oeuvre.

Unlike many architecture writers, McCarter understands the interior’s key role, particularly in Wright’s integrated work. While examining the houses in light of the architectural philosophy and principles, revealing the methods of construction and materials, and noting that Wright was always interested in new materials and advanced technologies, the interior is central to the discussion of all the houses included in the monograph. Living in Wright’s homes, he says, enables us to ‘rediscover something essential about ourselves,’ as he reveals themes such as the open, flowing interior spaces and the integration of furnishings into the overall scheme. This statement brought to mind my visit to Taliesin, Wright’s home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, which he built on the land of his mother’s family and where he spent time as a young boy.

I walked the estate grounds, explored the interior spaces, and experienced his life in the house, the circulation, the relationship between the rooms and between the exterior and the interiors, and the way he created the house as one integrated work. This Prairie House, so deeply entrenched within the midwestern landscape, was a kind of epiphany for me, as I finally began to understand more fully the great architect’s grand vision.

McCarter devotes much of his text to the interiors, which Wright famously called ‘the space within.’ On living in the Avery Coonley House in Illinois, for example, he writes:

The living room is one of Wright’s greatest achievements, a space of repose, as he defined it; the large, heavy, and massive fireplace balanced by the floating, folded, and rhythmically modulated plans of the ceiling – cave and tent,’ allowing his readers to experience the life lived in all of the houses included in the monograph, brining them to life through and breathing fresh air into them.

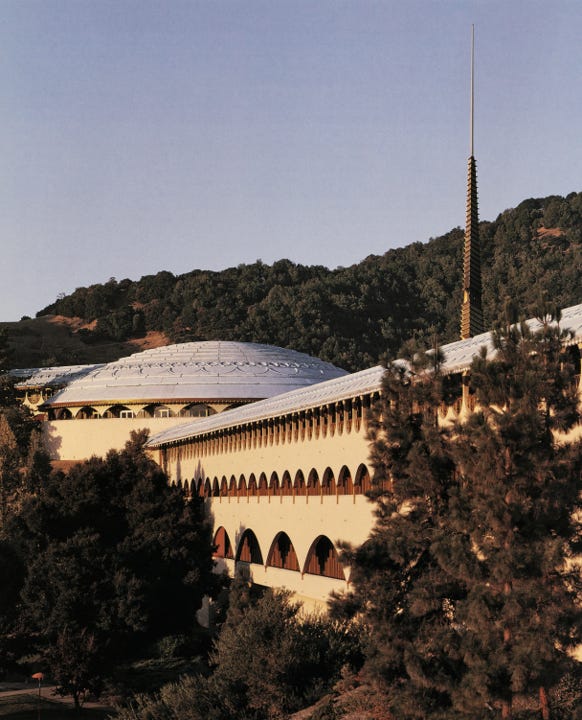

McCarter revealed that while the chronological sequence of Wright’s houses may have resulted in many different styles and modes, as well as the lifestyle of different eras, the basic principles and ethos never changed throughout his seven-decade career, and all of his houses possessed an American identity while being responsive to the site. Though he lived until 1959, to the age of ninety-one,’ McCarter says, “He was essentially a 19th-century man,” creating work that was organic, anti-urban, and unified. Wright remained loyal to the same philosophical design principles adopted early in his career, and which he had inherited from his 19th-century heroes. From Ralph Waldo Emerson, he took the Romantic idea that nature represents the divine; from Louis Sullivan, his first employer, the notion that organic architecture embodies the harmonious relationship to the site, the belief that nature could give a powerful form to architecture, and the quest for honesty in the buildings’ materials. From 19th-century reformers, he acquired the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the home as an integrated, complete work of art, which was devised in response to the Industrial Revolution. While Wright lived throughout six decades of the 20th century, he was a practitioner of 19th-century reformed ideas, but by no means a historic figure.

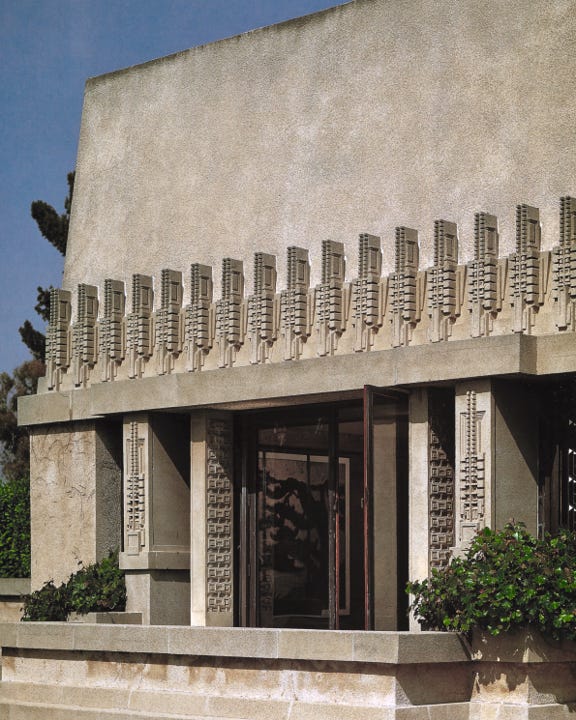

McCarter divides Wright’s houses into categories that embody their chronological and thematic evolution. The first section is devoted to Wright’s early houses, when he was fully inspired by early American cottages, blending them with his own innovations, best represented by his own house and studio in Oak Park, which McCarter calls his “first fully independent built work.” Then came the Prairie House, the name Wright coined to describe his American suburban homes, built to mirror the flat landscape of the Midwest, characterized by his iconic horizontal lines and open floor plans. McCarter calls the Prairie houses, which are opened toward expansive views and anchored by the heavy, solid hearths at their centers, “Extroverted Houses,” represented by the Cheney House in Oak Park. This single-story bungalow marked the end of Wright’s career in Chicago due to a scandalous public affair with Mamah Borthwick Cheney. The Courtyard Dwelling is represented by Taliesin; the Concreted Block House exemplified Wright’s patterned concrete blocks which resembled woven facades, as in his Ennis House in Los Angeles; the Anchored Dwellings are those houses which represented their powerful landscapes; and the Usonian houses were small and inexpensive, designed, starting in the mid-1930s, in response to the Great Depression, and built primarily in the countryside for small American families.

While Frank Lloyd Wright was a modern architect, always standing at the forefront of the modern architecture evolution, responding to the zeitgeist, he did not fit within the formula devised by Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock when the two curated their seminal MoMA exhibition of 1932, The International Style. Wright’s modernism was a distinct type of architecture, and his buildings did not subscribe to the internationalism promoted by the exhibition’s buildings. Philip Johnson famously called him the ‘greatest architect of the 19th century.’ The new monography is like a mini bible of the most famous architect of modern times, allowing the readers to fully understand his greatness and continuing appeal, and to virtually experience his transcendent spaces.