Frank Gehry (1929-2025) & Robert A.M. Stern (1939-2025)

The Friendship that shaped the two sides of American Architecture

The two most successful and influential American architects in recent memory, Robert A.M. Stern (1939-2025) and Frank Gehry (1929-2025), passed away last week within days of each other. Fortunately, before they passed, I had the honor of interviewing them both. One was a self-identified artist who turned architecture into an expression of contemporary art, while the other was an academic who discovered early American architecture and shaped it into his own personal language and into powerful architecture in both the city and the countryside. While Stern looked at the shingle style villas of 19th-century New England and the golden age of Manhattan skyscrapers of the 1920s, Gehry was on a quest to invent new, free-formed structures of a type never before seen in architecture, which were enabled thanks to the computer program CATIA. Born 10 years apart to working class Jewish parents—one in Brooklyn and the other in Toronto, later emigrating to Los Angeles. Both men have left a major mark on their hometowns and on architecture culture.

Stern and Gehry were distinctly different, not only in their vision and their iconic architectural vocabularies that became instrumental to the evolution of American architecture, but also in the way their careers emerged. Both glamorized architecture in their own voice, and both helped birth the term ‘starchitect.’ Both established their offices in the 1960s and built enormous practices; 300 employees at Robert A.M. Stern and 120 at Frank Gehry’s Los Angeles-based firm. When Stern was asked which architects he admired, he immediately responded with “Frank Gehry,” and added, “he was ‘A’ and I’m ‘B’, or Alpha and Omega.”

When Gehry completed the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in 1997, it was praised by all critics and was considered to be the first building of the 21st century. It proved that architecture could turn a sleepy city like Bilbao into a sexy tourist destination, that architecture alone has the power to bring an ordinary town to global prominence. When Stern completed his limestone clad, highest priced 15 Central Park West in 2007—or the ‘apartment house’ as he liked to call it—he proved that to capture the nostalgic imagination and love of New Yorkers who are willing to pay top dollar for the classic marble-columned lobby, wine cellar, private restaurant, and library, it was not the sleek glass towers which had been popular until then (notably designed by Richard Meier, Jean Nouvel, Charles Gwathmey, and Herzog and de Meuron), but rather an ingenious homage to Manhattan’s finest apartment buildings—even if it lacked the patina of celebrated Manhattan apartment houses such as the River House and Candela’s Park Avenue buildings. However, his traditionalism brought a lot of criticism. When Stern was appointed Dean of the Yale School of Architecture in 1998, students demonstrated against him, because his reputation caused fear that he would move the school away from its progressive, avant-garde legacy. But during his tenure, Stern generally won over his critics by embracing a pluralistic approach to education. One of the teachers during his tenure was Frank Gehry.

Both Stern and Gehry proposed alternatives to Modernism, taking part in the American Postmodernist movement. Yet, they produced distinctly different architecture. Gehry’s buildings are extravagant, dazzling, and memorable, while Stern built traditional buildings and houses that are quiet, classy, straight forward, and familiar; but not humble. For Stern, education was the force of his career, serving as the Dean of Yale School of Architecture for 18 years, while Gehry understood very early that he had to discard everything he was taught as a student at University of Southern California, which was the mid-century expression of Modernism. He discovered Romanesque architecture while living in Paris and working for the French architect André Remondet in 1961, which revealed to him that architecture could be grotesque, fantastic, spiritual, an emotional, of plasticity and irregularity, all concepts he would later revisit. This was the point of departure to his own radical architecture.

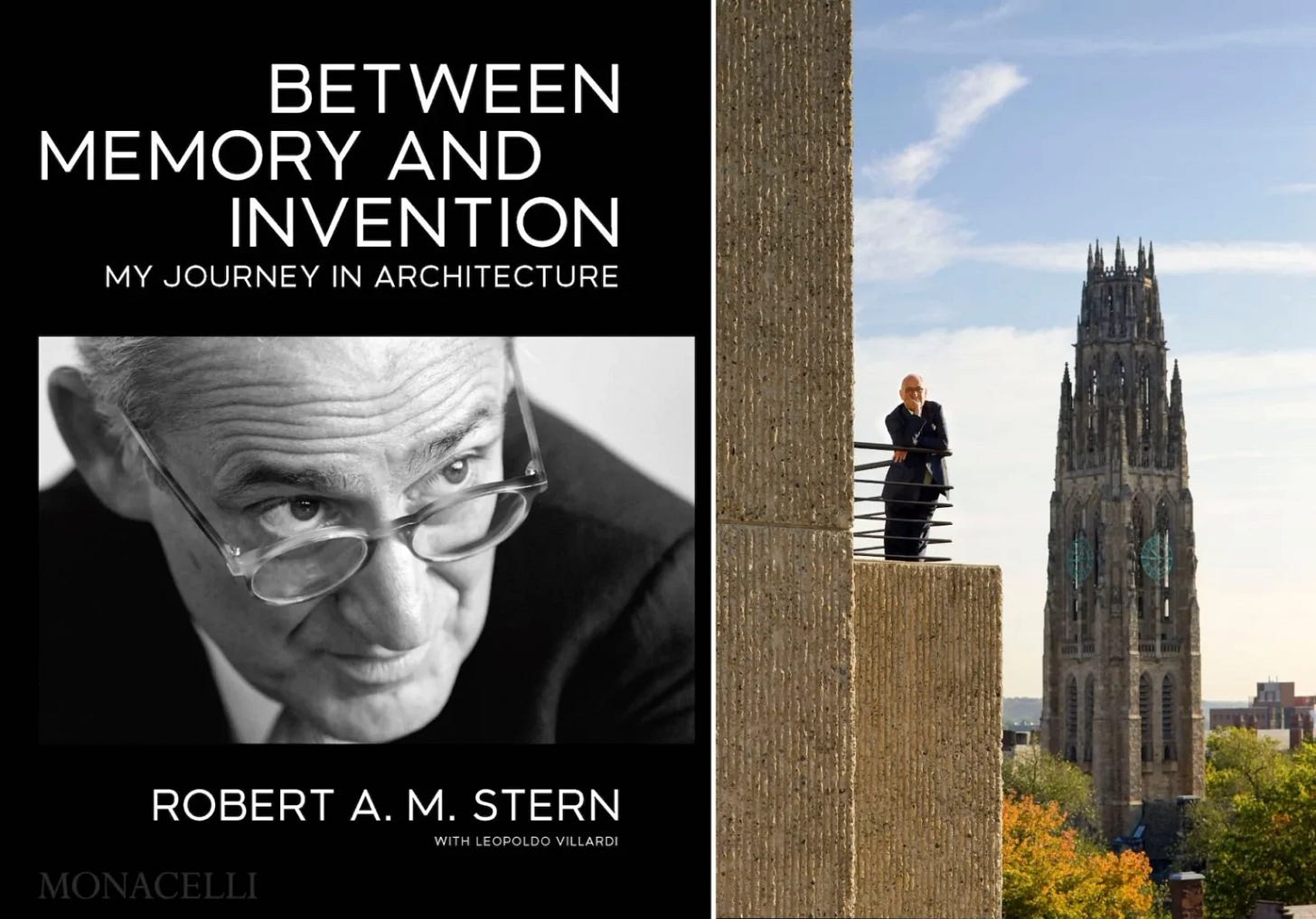

If you want to learn more about these two giants, I recommend two relatively recently published books. The first is Paul Goldberger’s definitive biography Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry (2017), which not only explores the evolution of Gehry’s career and personal life, but also brilliantly explains his greatness. The second is Stern’s autobiography Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture (Monacelli Press, 2022; reviewed by me). These two stars’ voices will remain in the narrative of the built fabric forever. Both extracted from history their own contemporary architecture and demonstrated that there is nothing like knowledge in history to construct new design identities and to shape the culture of the zeitgeist.