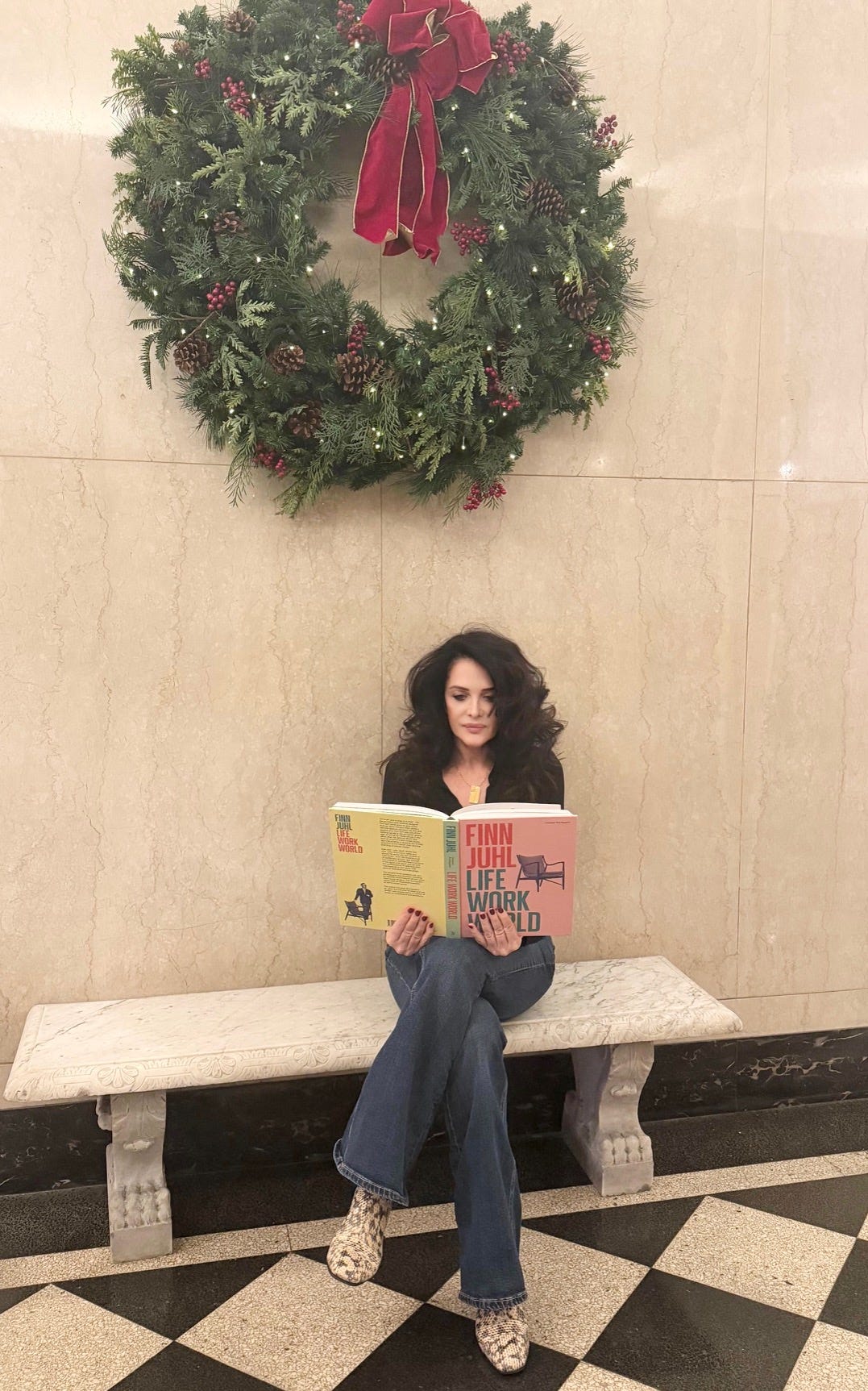

Finn Juhl: Life, Work, World

By Christian Bundegaard

Danish architect Finn Juhl (1912-1989) did things differently from his contemporaries. His maverick’s designs were not minimalist objects of simplicity, but rather bold, dramatic, and unconventional. Juhl’s innovative approach to furniture design was evident with his iconic chairs during the Golden Age of Danish Modern. If, according to British designer T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, a designer should consider it a career victory if he were to create even one successful chair in his entire career, then Juhl should be remembered as a genius. He designed not one but many successful chairs, which assured him a place in the pantheon of modern design, and he is often referred to as the guru of Danish furniture. Each of his designs took the form of a sculpture, each responded to the human body, and each encompassed a whole story. “One cannot create happiness with beautiful objects,” Juhl famously remarked, “but one can spoil quite a lot of happiness with bad ones.” His chairs were not only functional but also intriguing, capturing the imagination and attention of generations of design lovers.

“Scandinavian Modernism was particular to Scandinavia,” Christian Bundegaard told me. He was my recent guest in the season’s ‘Design and Architecture Masterpieces’ conclusion, in which we discussed his monumental monograph, Finn Juhl: Life, Work, World, just reprinted by Phaidon. Unlike the German modernists, who sought to forge design for the future by erasing the past, or the French, whose mission was to give design expression to industrial production, in Scandinavia, modernism had strong ties to tradition, providing a powerful sense of identity, belonging, and continuity, principles inherited from the godfather of Scandinavian Modernism, Danish architect and furniture designer Kaare Klint, who pioneered a new approach, focusing on human proportion and on collaboration between cabinetmakers and designers, and advocating the fusion of craftsmanship with functionalism, defining Danish Modern ethos and its unique spirit.

In Bundegaard’s monograph, we learn that Juhl elevated Danish design to post-war international status. He brilliantly demonstrated that a personal voice within the constraints of modernism should be celebrated because it had the potential to achieve design victory. “Four guiding principles stood at the core of Scandinavian Modernism,” Bundegaard said in our live talk, when defining Juhl’s oeuvre: “Utility and functionalism; minimalism and reduction; a use of local materials; and blending modern forms with traditional principles.” Juhl, however, added one extra principle to those practiced by his contemporaries—artistic expression. By combining art and design, he cemented his love of art through modernist Scandinavian design. His pieces were always playful and sculptural, as if he were creating dynamic sculptures that happened to have function. He radically departed from conventions and from the orthodox modernist idioms, expressing emotional resonance, immense power, and liberating furniture from its traditional appearance.

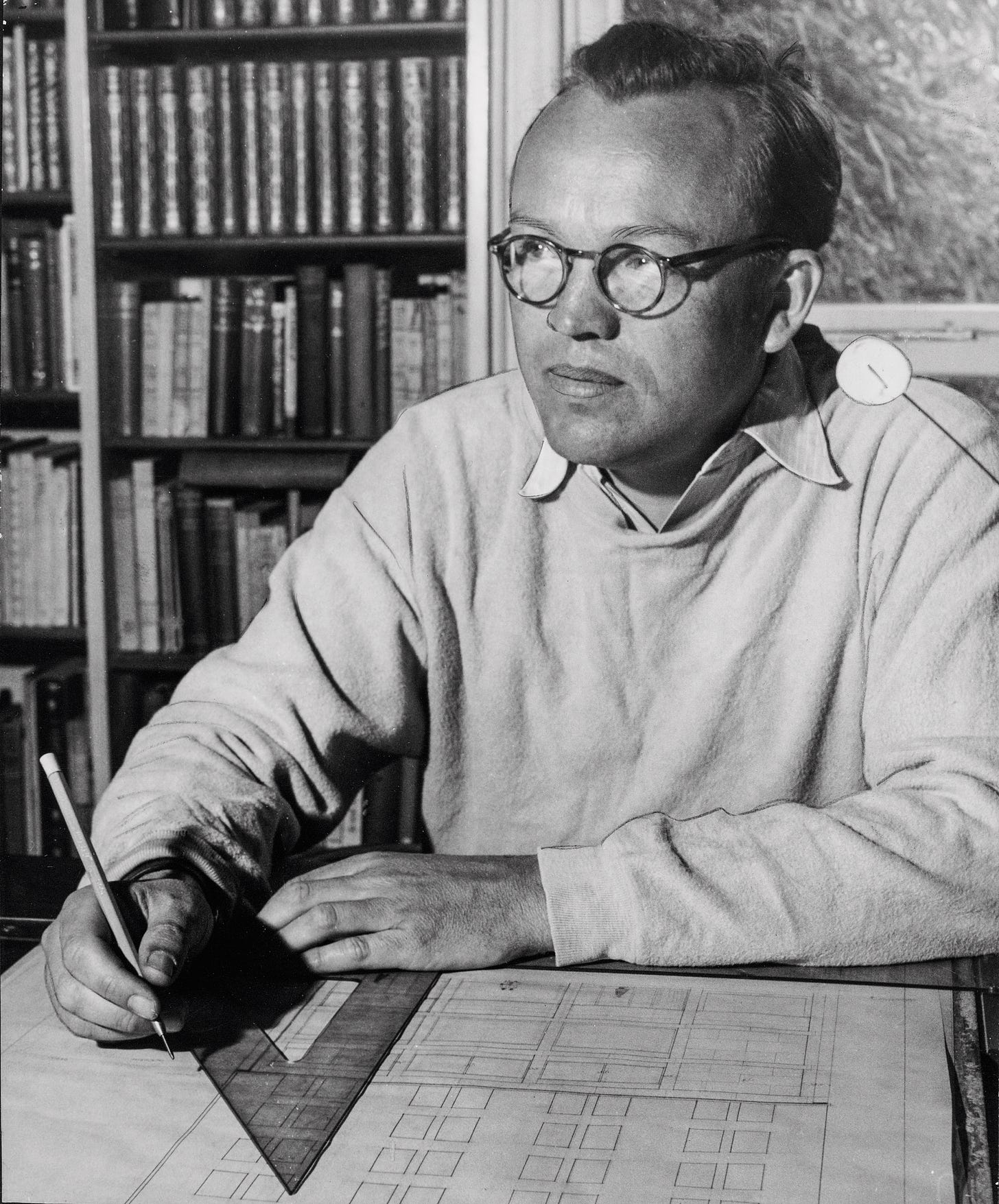

When investigating the roots of Juhl’s daring and unconventional approach to designing furniture, Bundegaard illuminates the architect’s passion for art which resulted in that unique expression. Juhl wanted to become an art historian, and it was his father who pushed him to study architecture. Upon graduating from the Department of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Arts in Copenhagen, he apprenticed at the office of modernist architect Vilhelm Lauritzen. When designing his highly personal house north of Copenhagen in 1940, the modernist principles were at the core of the program, along with the notion of a total work of art, as he sought to integrate architecture, furniture, and art as a unified whole. However, when Juhl began creating furniture, he became expressive and artistic, producing some of the most ambitious and intriguing pieces in the story of modern architecture.

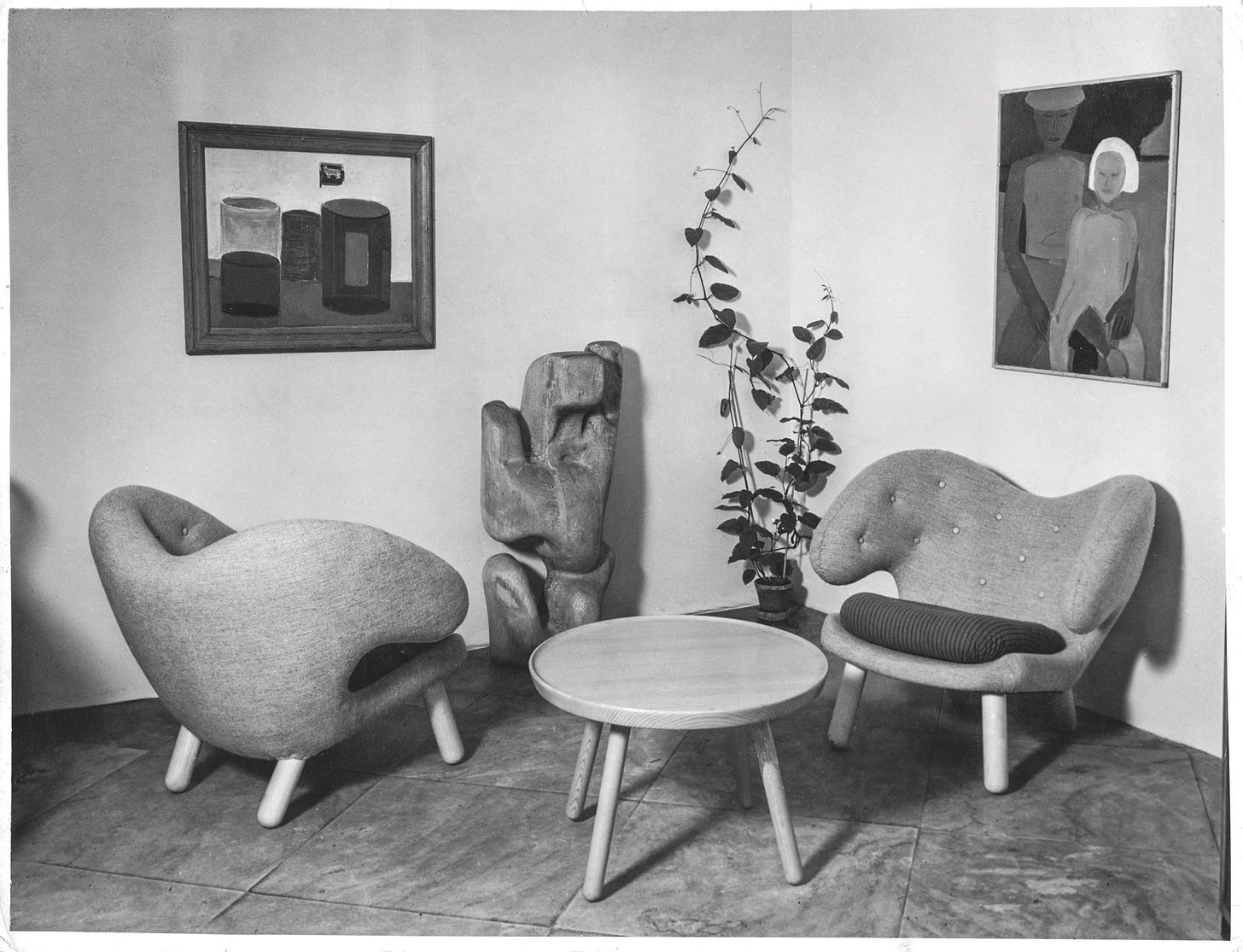

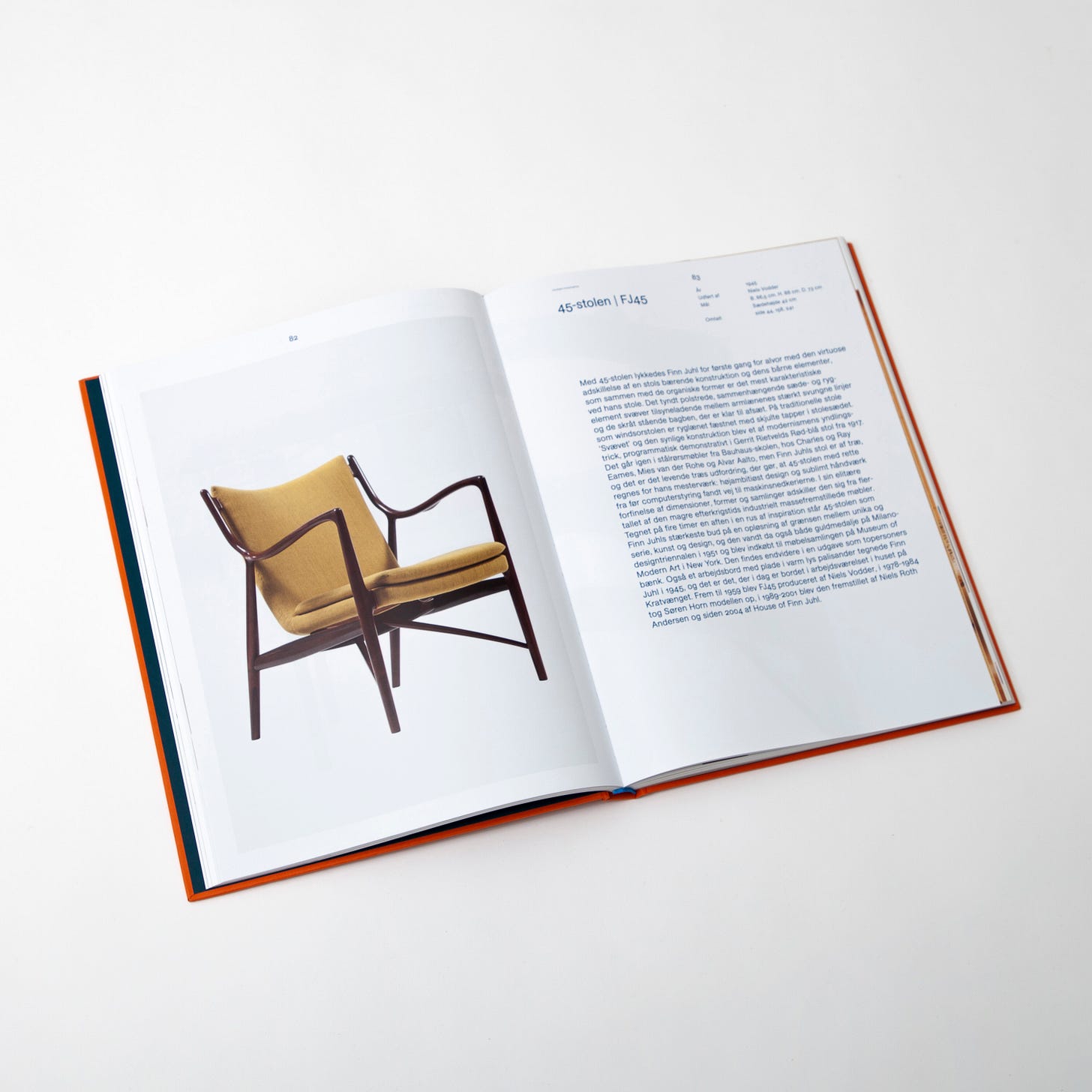

To create these ambitious pieces of furniture, Bundegaard said, Juhl needed a partner in the form of an exceptional woodworker and found the ideal partner in Niels Vodder. Vodder, considered the best cabinetmaker in Denmark, made a name for himself with meticulous attention to detail and with his ability to achieve refined forms. Employing only a handful of cabinetmakers in his workshop, Juhl had the skills and knowledge to bring Juhl’s complex pieces to reality. From the early years, Juhl was interested in ergonomic and complex forms, as seen in his playful Pelican Chair, his best-selling work, which suggested the form of the white waterbird. His Egyptian Chair was inspired by an example found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, and in FJ45, his most elegant, he successfully separated the bearing construction from the borne elements. No other chair has captured as much attention as his Chieftain Chair, introduced at the 1949 Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition in Copenhagen and executed in Brazilian rosewood, considered his most accomplished chair: complex, flowing, combining comfort and art, while transforming the armchair into a tribal sculpture.

What brought Juhl onto the international stage was his meeting with Edgar Kaufmann Jr., who headed the Department of Industrial Design at the Museum of Modern Art. Kaufmann was on a study tour in preparation for an exhibition on Scandinavian design when he met Juhl at the sale exhibit of Danish design at City Hall Square in Copenhagen. Upon his return, Kaufmann published an article in the magazine Interiors, titled ‘Finn Juhl of Copenhagen,’ when he first introduced him to the American public. Kaufmann visited Juhl at his home, and Juhl visited Kaufmann at Fallingwater and at his house on the Greek island of Hydra. The 1948 meeting launched a lifelong friendship and a successful career in the US. Juhl signed a contract with the Michigan-based furniture manufacturer Baker, created the interior of the Georg Jensen Inc. shop on Fifth Avenue, and was selected for the prestigious project of designing the Trusteeship Council Chamber at the UN Headquarters. During the 1950s, Juhl gained international acclaim as the leading exponent of the golden age of Danish design.

As interest in Danish furniture declined in the late 1960s, Juhl’s career faltered, and his furniture ceased production in the mid-1970s. But when he turned 70, he was fortunate to witness a revived interest in his work, kick-started with a retrospective at the Kunstindustrimuseet (Designmusem Denmark) in Copenhagen, before his passing in 1989. Bundagaard’s book Finn Juhl: Life Work, World is the definitive publication of the designer who wanted to be an artist and ultimately epitomized art in Danish Modern.